The top executive of Acteva, a San Francisco-based payment processing company, says he has a plan to dig out of $4 million to $5 million in debt and repay online donations owed to nonprofit organizations across the country.

Still, some creditors — including a community college, an environmental group, an agricultural cooperative and a regional journalism organization — said they were owed tens of thousands of dollars each, and questioned whether the business will ever refund the money. Some are now taking legal action.

CEO Pankaj Gupta said Acteva’s financial woes were due to a cash-flow problem, and that he would be able to pay back the funds by taking on additional paying clients and developing new software products. But he complained that high legal fees and bad publicity from a website created to criticize the company were making it hard for him to fix the finances.

“The plan is to avoid bankruptcy and keep the business going because we don’t have liquid assets,” Gupta said. “I have some nice deals that I’m in the process of sealing that could potentially give me nice cash.”

But irate customers across the country said they were doubtful about being repaid. Some nonprofit organizations that have used Acteva’s services claimed that they had not received their checks for months.

Lori Weisberg, a board member of the San Diego chapter of the Society of Professional Journalists, told ABC7 TV in October that her group had not been paid thousands of dollars raised in a fundraiser earlier in the year. “This is a company that caters mostly to nonprofits organizations that can least afford to have this kind of financial hit,” Weisberg said.

The complaints have led to at least one criminal investigation and several civil claims. The San Francisco District Attorney’s Office confirmed that it had opened an investigation, and said it was accepting reports about the company by phone at (415) 551-9558.

Although it is not one of the top online payments processing firms nationwide, Acteva, which was founded in 1998, is a popular choice for businesses and nonprofit groups raising money for event registration or online donations. By 2010 the privately held company claimed that it had more than 17,500 customers and processed $800 million in registration receipts. The firm also provides office management services for events, fundraisers, conferences, meetings and training programs.

After collecting and processing credit card information, Acteva says it keeps a small percentage for itself before returning the rest to the customer. The process is supposed to take up to six weeks, depending on the size of the event, number of tickets sold and credit card cancellations.

Clients are given the option of collecting online credit card payments through their own Internet merchant accounts at an additional cost, or saving money and collecting payments through Acteva’s default merchant account. Many of those customers saw delays in payment.

Now it appears that the payment problems have led Acteva to disable some of its services. A notice on its website reads, “Acteva Payment Management Services are currently unavailable.” The company did not respond to questions about who, if anyone, was still using the company’s payment and registration services

Clients and online activists who have complained loudly about the company said they doubted Acteva’s plan to resolve the payment delays.

“At this point it’s more beneficial to have them completely shut down,” said Jason Brown, who created the website actevasucks.info, a gathering place for customers to compare notes and vent their frustration at the company.

Brown said his wife’s organization, which he declined to name, signed up for Acteva in October 2012 to handle registration for an event in April 2013. The company was obligated to process credit card payments, keep a portion of the income and return the rest. But the money was slow to come back, and at one point Acteva owed the group $65,000, according to Brown. Now, he said, his wife’s organization is still owed $18,000.

TARNISHED REPUTATION

Gupta said Brown’s website and the bad press were killing Acteva’s brand and its ability to repay creditors. But he said that if he could figure out how to manage the negative publicity and grow the business at the same time, then organizations would get their money back. He said Acteva was seeking to hire a professional public relations consultant.

But the company has had to fend off multiple claims from creditors, and now the company’s legal fees are higher than its revenues of roughly $5 million to $6 million this year, Gupta said.

Acteva’s lack of cash led it to miss rent payments on its downtown San Francisco office, which employed roughly 40 people as recently as November 2012. After downsizing, Acteva’s five remaining part-time employees now work remotely.

The company says in promotional material on its website that it is committed to customer service: “Acteva specializes in ‘actively listening’ to its customers.”

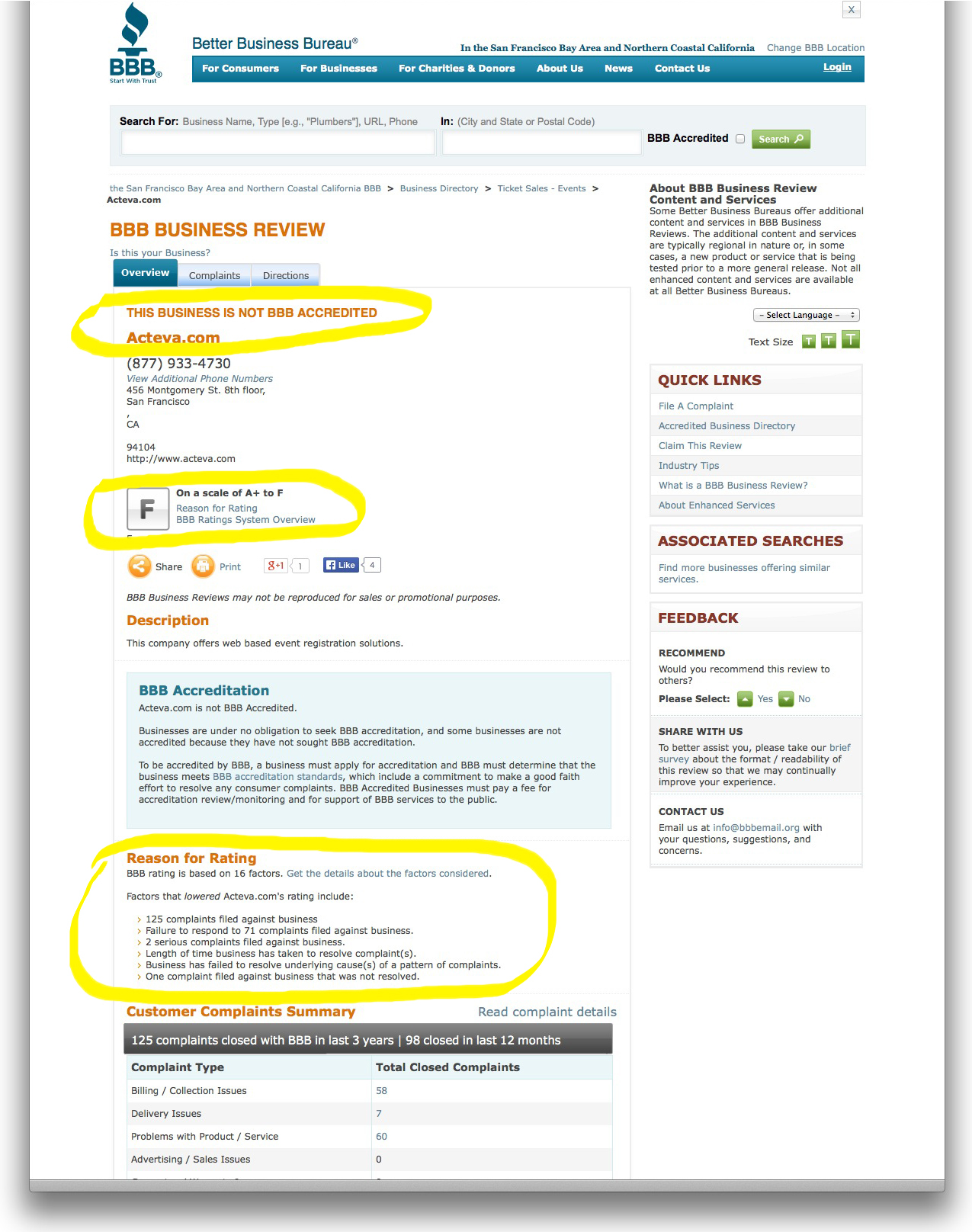

But aggrieved customers say Acteva has ignored numerous phone and email inquiries about their money. The failure to respond to complaints led the Better Business Bureau to revoke Acteva’s accreditation as a reputable business. (Acteva’s file on the bureau’s website does not give a date, and the organization said it could not provide a timeframe for the reviews.)

Gupta, who has run the company since 2001, offered several explanations for the debacle. He attributed the firm’s woes to economic recession, Hurricane Sandy and a sick executive.

When asked where the payments Acteva was processing ended up, Gupta said the money was used to run the business and to refund money owed to other customers.

“We got caught up in a tsunami,” Gupta said. He insisted that he never meant to cheat his clients and that he intended to rectify the problem.

CREDITORS UNIMPRESSED

Many current and past customers are not convinced. Susan Soergel’s organization, the Boston Chapter of the Power and Energy Society, held an event in the fall of 2012. By February 2013 it was still owed $19,000. With the help of a lawyer, her group got all its money back.

Soergel said in an email that she was “aware that Pankaj is blaming others (including Mother Nature) for Acteva’s problems, but I’m not buying it. They drove that company into the ground by not responding to their customers and/or feeding them misinformation as to what was going on and when they would get paid.”

Acteva’s former vice president of sales, Dave Ghosh, said that he was not responsible for client collections or reimbursements. But he said he was part of a failed internal effort to repair the backlog.

“I learned in early 2013 that some Acteva clients were not being properly reimbursed,” Ghosh said. “I attempted to remedy the situation but resigned from the company when it became apparent my efforts were unsuccessful.”

Another former employee said that in the spring of 2012, Acteva had about 50 employees in San Francisco and 80 in India, but disorganized management and customer complaints resulted in a high employee turnover rate and many layoffs. The employee, who asked not to be identified for contractual reasons, also described the working relationship between Gupta and Ed Lemire, the company’s vice president, as “weird,” saying the two argued constantly.

BANKRUPTCY POSSIBLE

Acteva’s clients might never get their money back, even if an investigation discovers criminal wrongdoing. Karen Gebbia, a law professor specializing in bankruptcy and corporate law at Golden Gate University, said that if a business has few or no assets, little or nothing is left to refund to creditors.

“A business with a viable business structure may file Chapter 11 bankruptcy in an effort to restructure its obligations and pay its creditors, at least in part, over time,” Gebbia said.

But, she said, the process breaks down when cash reserves have disappeared: “Attempting to compel equitable distribution is not particularly useful if there is nothing to distribute.”

Gupta’s plan to avoid bankruptcy by taking on more clients does not sit well with Brown, who said the strategy could cause more customers to get caught up in Acteva’s cash-flow problem. For now, Gupta and his employees are not talking in any detail about their new business plan.

Gupta said most creditors are nonprofit organizations, and some clients in the sector speculate that they were targeted by Acteva for nonpayment. Not everyone agrees with that assessment. Some experts in nonprofit management say smaller organizations in general are more vulnerable to delays in repayment.

“Getting into a situation like this, I don’t think, is related to the nonprofit structure,” said Jan Masaoka, CEO of CalNonprofits, a California membership organization that advocates on behalf of charities. “But maybe the consequences are more far-reaching for nonprofits than they are for a private business of the same size.”