San Francisco should move people living on the streets to the top of the list for permanent supportive housing, advocates and service providers said Tuesday.

The current system of setting aside all available housing units specifically for homeless people living in shelter-in-place hotels is not proving effective, advocates and city officials said at a hearing of the Board of Supervisors’ Budget and Finance committee. More than 2,000 homeless people currently reside in hotels, which are paid for by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to mitigate the spread of COVID-19.

People in hotels often reject placements in permanent housing because of the cost and lack of privacy, among other reasons. Partly as a result, nearly one in 10 permanent supportive housing units sit vacant.

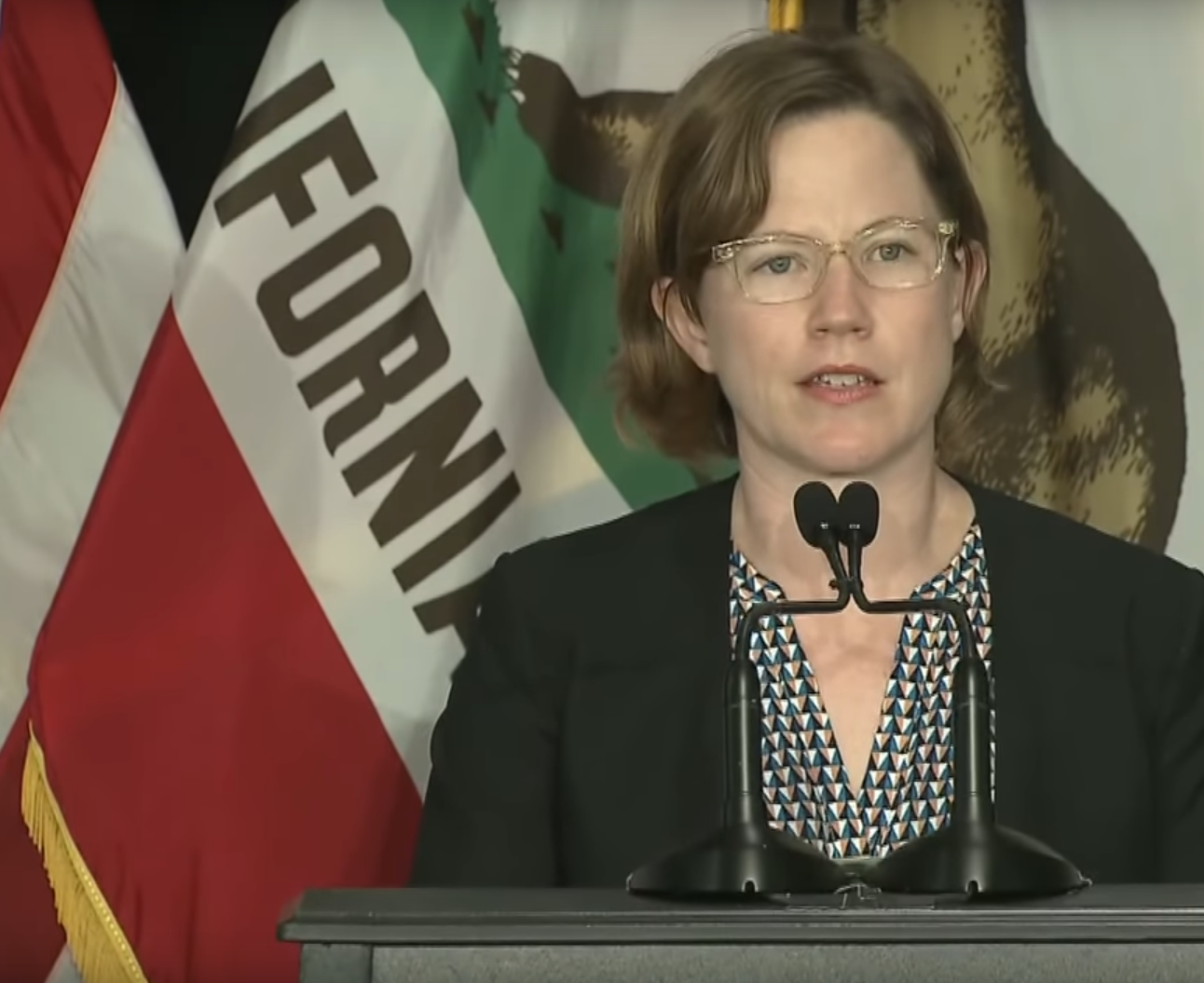

Seventy percent of shelter-in-place hotel residents have rejected housing in the Granada Hotel — a newly converted, 232-unit permanent supportive housing building the department is trying to fill, according to Abigail Stewart-Kahn, the interim director of the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing.

“This is understandable,” Stewart-Kahn said. “We’ve never had shelter that in many ways is nicer than our housing portfolio.”

The pandemic-era decision to offer permanent supportive housing units only to people who reside in shelter-in-place hotels was made in response to pressure from the Board of Supervisors, the mayor’s office and the community at large to move people from the hotels into housing instead of to the streets when the program ends.

As a result, the 626 people who have been approved for permanent supportive housing who live outdoors are now at the bottom of the list, behind the 594 shelter-in-place hotel residents who have also qualified.

The city has gradually been offering hotel residents housing, but many choose to remain where they are. Shelter-in-place hotel rooms are free for residents, have private bathrooms and come with three meals a day. In permanent supportive housing units, residents pay rent and often share bathrooms with neighbors in the building. Most permanent supportive housing buildings do not have kitchens, and residents aren’t provided free meals.

But Mary Kate Bacalao of Compass Family Services said the Department of Homelessness and Supportive Housing misinterpreted providers’ request at the beginning of the pandemic to ensure people living in shelter-in-place hotels can access housing.

“We did not intend to put unhoused people who had already been waiting in the system for housing at the end of a 2,200-person line,” she said, later correcting that figure to 1,220.

Stewart-Kahn said the department is re-evaluating its policy. But she is hesitant to renege in any way on the city’s commitment to housing people in shelter-in-place hotels.

“The tradeoff here is if we move too many permanent supportive housing units away from the shelter-in-place hotels, we won’t be able to provide offers of permanent housing to people in the hotels,” she said.

In the meantime, the number of residents in shelter-in-place hotels is rising. As a result of the hearing, the Budget and Finance Committee approved a 60-day emergency ordinance to bring about 500 more people off the streets and into shelter-in-place hotels. If the full Board of Supervisors passes the ordinance on Tuesday, March 2, it would force the Department of Homelessness to reverse its policy and being moving people living outside of the hotels who’ve prioritized for housing into vacant units.