Part of a special report on homelessness and mental health in San Francisco, in the fall 2014 print edition. Stories rolling out online throughout the fall.

For a decade, San Francisco’s answer to homelessness was “housing first.” Get people off the streets and out of shelters, the theory went, and their lives would improve dramatically.

But this year, as city officials and social service providers congratulate one another for ticking off many bullet points in an ambitious 10-year plan to “abolish chronic homelessness,” they are facing a stark reality: The situation does not look much better than it did in 2004.

Now they are trying to reform a fragmented, overextended public welfare bureaucracy that has not demonstrably reduced homelessness. Thousands of people remain in shelters or on the streets because the city’s supportive housing program does not have enough rooms to go around.

Placement into subsidized housing is a messy process in which persistence, luck and likability are important factors. Instead of waiting list, the city has several “access pools.” This means that when people ask for housing, they cannot predict when their names might be chosen. While housing is reserved for the sickest and the most chronically homeless, someone who is sicker than those already on the list can jump to the head of the line.

For years, it has been up to city staff to review one case at a time when a vacancy opens up. Nonprofit housing contractors are often in the position of cherry-picking which clients they serve, said caseworkers who work with the formerly homeless.

Officially, just under 1,000 people are now assigned to these pools for some form of supportive housing. But city officials say they are not sure how many people are eligible for supportive housing at any one time.

Although city agencies have intake files on thousands of candidates for housing, they stop adding names when the access pools are filled up. With only a few hundred spots opening up each year, there is no point in creating larger lists.

“Right now, because of the competition for housing, most of what we do is just scramble at vacancies,” said Bevan Dufty, who now runs homelessness programs for the Mayor’s Office of Housing, but lacks direct control over policies and budgets. “We need a system that is better coordinated, and we should be assessing people and placing them in housing that best meets their needs.”

Sharon Christen is a housing developer with the nonprofit Mercy Housing California that under contract with city agencies manages 33 housing sites. She said supportive housing programs have few openings. “When they’ve gotten to us, they’ve won the lottery,” she said.

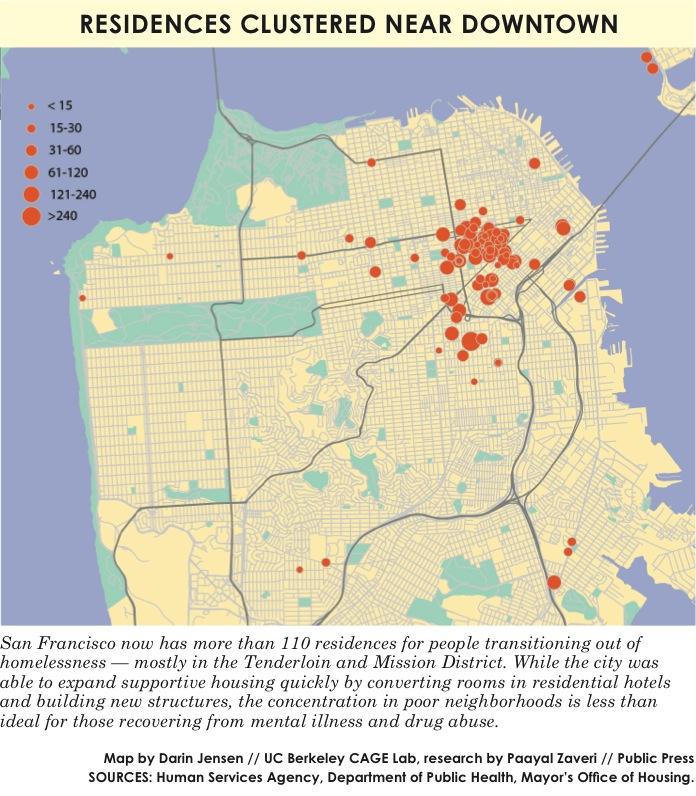

But those who leave the streets through the city’s programs often land in neighborhoods plagued by poverty and crime. To control costs, the city established most supportive housing in converted single-room occupancy hotels in the Tenderloin and other areas where the drug trade was rampant. But one side effect is that it has made it easier for people with addiction to relapse.

Nonprofit care professionals say formerly homeless people who need help with more than just housing often end up in residences that cannot provide them with adequate security, psychological support, medicine, life-skills training or conflict mediation.

Caseworkers are often burdened with heavy caseloads. Once housed, the city signs contracts with six primary nonprofit housing organizations, which are required to link tenants with caseworkers. The nonprofits also employ front-desk clerks and property managers. While city agencies do not require providers to report how many caseworkers or support staff are assigned to tenants once they receive housing, representatives at eight of 10 nonprofit organizations reported caseloads ranging from 25 to 110.

Even though city departments do not track data on the number of caseworkers per building, a survey of the nonprofits that operate nearly 3,000 units scattered around the city found that in at least three buildings, a single caseworker supervises more than 100 people. Experts in supportive housing say industry best practice is one caseworker per 30 residents.

The biggest structural challenge to getting homeless adults into the right housing is that two big city departments, the Department of Public Health and the Human Services Agency, run parallel referral systems. They do not share client lists, making it hard for people to move among different types of residences with a variety of supportive services.

INFOGRAPHIC: Two city departments run similar programs focused on getting people off the streets and into housing. Audits of San Francisco’s homelessness programs say that the demand for permanent supportive housing far outstrips supply. More than 7,000 people are homeless today; only a few hundred spaces in housing become available each year. Illustrations by Patrick Sean Gibson.

While Mayor Ed Lee this summer proclaimed the 10-year plan a success, behind the scenes his administration has been working since at least February to reform the system to make sure it better triages placements based on need.

Roughly half of the city’s housing providers are planning to roll out a new computer system to sort applications according to the severity of the illness of the applicants. Some housing organizations are also starting to use a tiered model to match the neediest clients with the most intensively supervised facilities. A common intake form would also streamline referrals from street outreach workers, hospitals and drop-in clinics.

But it is unclear what difference that will make for clients stuck in a murky access pool. With about 95 percent of tenants in some of these programs staying housed each year, opportunities to leave the streets are rare because low turnover results in few vacancies.

The city has invested heavily in its housing-first approach over the last decade, expending roughly $200 million each year for all homeless programs. But this has not cured homelessness in San Francisco. Counting the homeless is a notoriously difficult challenge, but Harvey Rose, the city auditor, said the best data show 7,300 people in 2013 — not drastically different from the 8,640 recorded 10 years ago.

The city’s most common defense is that things would have been much worse without its efforts to get chronically homeless adults indoors. The mayor’s office said the city placed 11,362 people in permanent supportive housing in a decade.

Those who have received their own space behind lock and key at least get the chance for a recovery. Still, there are many more losers than winners in the complex competition for basic housing.

For three years, a talented tenor whose voice earned him the street name Opera, and his girlfriend, Melinda Welsch, have sought a placement from the city, they said.

Most nights, the couple sleep in and around the Civic Center BART station, and sometimes are roused from their sleep — depending on the mood of the police.

But their friend, Terrence Smith, lucked out. He had lived on the streets for more than a decade, most recently in the Tenderloin.

“I remember when I got the call, it didn’t sound real,” he said. “For years, I slept out here. I got to the point where I didn’t care about nothing.”

Smith, 46, said he was always comfortable on the streets and survived on about $700 per month in disability pay. “I was wearing the same clothes for five, six days in a row,” he said, “I hadn’t shaved in weeks. I was in a bad place.”

Then his number came up. In December Smith was selected as the first tenant at the new Rene Cazenave Apartments, a bright, eight-story, 120-unit building in South of Market for people with severe mental illnesses, substance abuse problems or other complicated health issues.

Smith, who has bipolar disorder and HIV, was meeting with a caseworker regularly and getting medical treatment. But it was hard for him to stay on his medications and remain psychologically stable while living in a homeless encampment near the Bay Bridge and in shelters. The new apartment, he said, “saved my life.”

Who Deserves Housing?

Candidates for supportive housing programs get referrals through institutions frequented by the homeless, such as the San Francisco General Hospital emergency room, the county jail or psychiatric hospitals. But most of those deemed eligible never get off the streets.

At the Department of Public Health, the supportive housing access pool is capped when it grows too large, and after that only clients with the toughest cases get in. The department has adjusted the cap repeatedly.

In January 2013, the pool had 700 names. At that time, only about 30 housing slots opened each month. A year later, the pool reopened, but it closed six months later, after swelling again to 700. In September, public health staff said the pool had 500 names. By October that estimate had fallen to about 300, said Margot Antonetty, director of housing and urban health under the Department of Public Health.

City officials said they had no way of knowing how many people were waiting for housing. In part, that was because the city and the permanent supportive housing providers it funds mostly phased out chronological waiting lists starting in 2005, and adopted a more complex system that requires city staff to make subjective evaluations and negotiate with site managers over where to place each person.

“We have learned to close our referral pool when it gets that high because we assess by need in terms of assigning the units,” Antonetty said. “You can’t track people at all times in terms of what their need is like when it gets higher than 500.”

The process of getting into the access pool is haphazard. Case managers are sometimes influential in advocating for a client to get into an access pool. Those deemed eligible for housing can be skipped over when a needier client appears.

Candidates are judged by city staff on how many city services they use, including the emergency room, Laguna Honda Hospital’s Psychiatric Emergency Services unit and the Homeless Outreach Team that regularly canvasses the people living on the street.

Caseworkers then contact city officials or nonprofit managers, who select which clients they want to offer spaces based on the level of need and services available in their buildings. Because caseworkers try to ensure tenants match the character of each site, providers are sometimes motivated to accept residents who will cause the fewest problems, making it hard for the most troubled clients to find housing.

Advocates for the homeless say the lack of predictability complicates an already difficult existence for prospective tenants, particularly those suffering from mental illness who have difficulty organizing their thoughts and advocating for themselves.

“It’s all part of a negotiation from the very beginning,” said Christen, the developer with Mercy Housing. “We’re going to get referrals, and we determine whether we can take that person based on the services we have, but we don’t really have the capacity to deal with people who are super high need.” Antonetty said the biggest need in reforming the system is to make sure those in need get priority. Waiting lists do not work, but the current setup is not perfect.

“We needed to centralize our access system,” she said, “but the question was how do we do that and continue to prioritize those who are the hardest to serve or to reach.”

Bottomless Pool

There is clearly not enough supportive housing in San Francisco to rescue everyone from the streets. Of 7,350 homeless identified last year, 4,315 did not have access to a temporary bed. Rapidly rising rents across the city in the last three years have made it only more costly for the city to expand these real estate investments.

In dozens of interviews with housing providers in recent months, city workers, contractors, social service providers and people formerly living in homelessness said the city never had the money or the staffing to provide housing for everyone who needs it.

“The demand for this type of housing far outstrips the supply,” said Don Falk, executive director of the Tenderloin Neighborhood Development Corporation. The nonprofit housing developer manages 2,500 housing units in San Francisco, one-quarter of which are for the chronically homeless.

“We turn away people routinely,” Falk said. “We field queries every day from people looking for housing, and we can rarely accommodate anyone new.”

The whole homeless services infrastructure, in fact, has been bursting at the seams at every level for years. The roughly 1,500 shelter beds at four primary emergency shelter sites throughout the city are at capacity.

“Our shelters are 98 percent full every night,” Dufty said. “And even with 3,000 new units, it’s clear that we do not have enough permanent supportive housing. I agree that there’s far more people waiting.”

What is clear is that after the Great Recession stalled San Francisco’s economy, the subsequent tech boom attracted a wealthy demographic, exacerbating the divide between rich and poor.

A study this year by the Brookings Institution found that San Francisco has experienced the greatest increase in income inequality in 35 years. “In San Francisco, skyrocketing housing costs may increasingly preclude low-income residents from living in the city altogether,” the report’s authors concluded.

With real estate prices rising, the city has had trouble acquiring and building more supportive housing. Over a decade, San Francisco departments and private housing developers have built or acquired 2,699 permanent supportive housing units for the chronically homeless; 407 additional units are scheduled to come online by 2017. Beyond that, the city has not officially committed to spending additional money to build or purchase new permanent supportive housing units. It allocated $29 million this year to fund other homelessness services, such as eviction prevention, housing services for transitional-age youth and mental health care, according to the mayor’s office.

The housing crunch has created a bottleneck, because people living in subsidized housing of all kinds rarely leave by choice. The city’s waiting list for federal Section 8 low-income housing reached capacity years ago and remains closed.

Harvey Rose, the city auditor, said in a report last year that housing scarcity was undercutting the intended health and economic benefits that made the housing-first policy attractive.

“There is a limited supply of permanent supportive housing, and it is often obtained by one person at the exclusion of another,” Rose wrote, adding that city staff must reserve spaces for “the extremely vulnerable.”

Homelessness, Rose concluded, is a moving target that eludes easy fixes: “The effect of the city’s permanent supportive housing production on the size of the homeless population is unknown, as the number of homeless persons might have grown larger in the absence of these new supportive housing units.”

And so thousands wait, in bare-bones shelters at night, concentrated in the city’s grittiest neighborhoods. Social workers who reach out to these populations say these conditions contribute to more addiction and mental illnesses.

A Life Reclaimed

The Tenderloin is eight-by-eight blocks of prime real estate in the heart of the city. Protected by strict zoning and housing affordability laws, it has become a haven for the homeless. Nearby, construction cranes dot the skyline. A rough count in early May tallied 14 buildings in the core of the city that were under construction. In the Tenderloin, people live in poverty, but find access to an array of services — from methadone treatment, to free lunch at St. Anthony’s, to a safe place to sleep at St. Boniface Catholic Church during daylight hours.

Most days, at the church, more than 100 people sleep sprawled on the floor and in pews amid a faint fog of incense until the late afternoon.

Terrence Smith spends most of his days in the Tenderloin. He gets free lunch at St. Anthony’s soup kitchen and catches up with friends on street corners. He spends a lot of time scrounging up money for cigarettes or a burger.

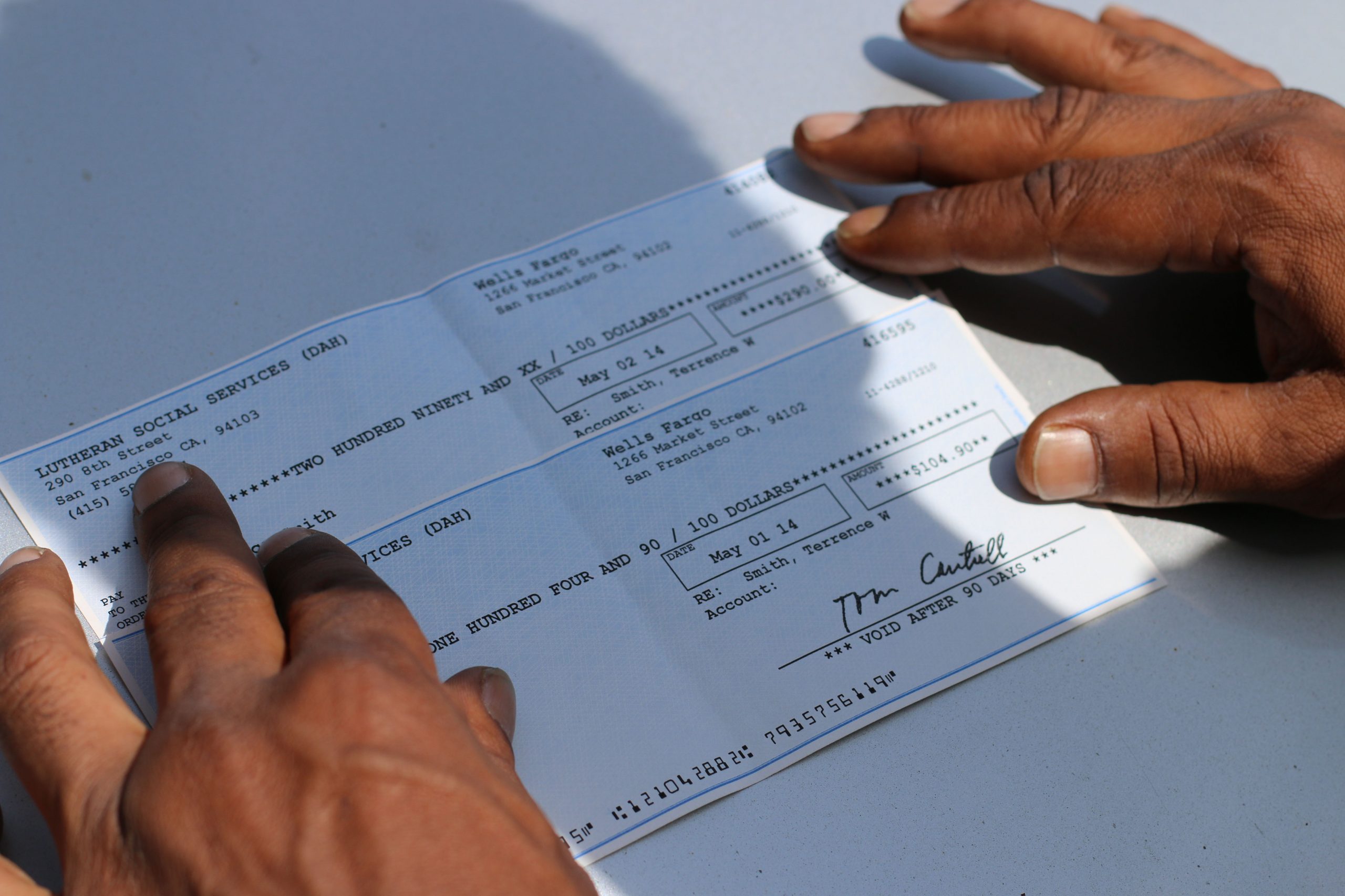

The Rene Cazenave Apartments, in SoMa, has 120 units overseen by the Department of Public Health dedicated to housing the chronically homeless. Rent is no more than 50 percent of monthly income, and it is automatically deducted from welfare or disability payments. Checks for the remainder come at the start of each month.

It is clear when the beginning of the month rolls around in the city’s Mid-Market neighborhood. By 11 a.m., when check disbursal begins, a line stretches three blocks around the corner from the pickup spot at Lutheran Social Services on Eighth and Folsom streets. Smith, who goes by the nickname Kali, knows everyone. He is “of the streets,” as he likes to say.

After rent is deducted from his disability payments, Smith is left with nearly $400. He is no longer homeless, but he is still poor.

“Man, I’m going to have to hit St. Anthony’s a bunch this month,” he said, “I can’t afford to eat on this.”

Smith’s housing situation helps him keep his health on track. Every morning, he takes six anti-retroviral pills that keep him from developing AIDS. “I got to take them before 10 a.m. — otherwise, I’ll start to feel sick,” he said.

Jumping aboard the N-Judah train to the Inner Sunset, he went to see his caseworker at the University of California San Francisco’s Men of Color Program, an HIV and AIDS treatment center. Sherman Woods, the head case manager, said they got to know each other when Smith hit bottom two years ago.

“We reached out to him because he was in desperate need of help,” Wood said. “His viral load was out of control, and he hadn’t been to the doctor in years. Like most African American men, Terrence had severe mistrust for doctors. There’s such a stigma associated with HIV and AIDS that we have to do whatever we can to get through. That, mixed with poverty, was making life nearly impossible for him.”

Woods put Smith on a strict mental and medical regimen. He gave him Safeway gift cards for food so he could eat healthily, even though he was sleeping outdoors.

“It took awhile to get through to Terrence,” Woods said. “We had to stabilize him — get him to understand the importance of adhering to his medication schedule. But the most important thing I think we did is get him into housing.”

Woods worked his connections at the San Francisco AIDS Foundation and the Department of Public Health to find Smith housing. That gave Smith the drive to follow up on housing applications with housing providers in the Tenderloin, sometimes inquiring in person after praying at St. Boniface.

At his monthly appointment, Smith embraced Woods, telling him, “You’re like a father figure to me.” Outside the clinic, he lit a joint and elaborated: “Sherman tells me to calm down when I’m having a bipolar moment. He helps me keep my appointments. I gave up on all this before I met him.”

Smith is also fortunate to have help in his apartment building. At the Rene Cazenave, four case managers tend to the needs of 120 formerly homeless tenants — a ratio of 30 to 1. The bright, modern building is staffed with a full-time nurse and a part-time psychiatrist to help administer medications.

Caseworker Shortage

Across San Francisco, however, many residential programs for the formerly homeless are understaffed.

Marla Smoot, a caseworker at the Jefferson Apartments on the corner of Hyde and Eddy streets in the Tenderloin, provides case management for 110 residents.

She helps tenants work through behavioral health issues, including hoarding, cluttering and violent outbursts. She also provides counseling, job placement and legal referrals in eviction cases.

“I see people with more simple needs,” Smoot said. “I had a guy ask the other day where to find a notary public, and another guy who always wants to know the price of gold. So we’d just Google the price of gold.”

Some days her workload is very different.

“Other times, I’ll have more serious situations, where tenants will want to talk about getting a mental-health provider, or maybe they want to go into a substance abuse program.”

Her phone rings constantly — typically 10 phone calls in a 30-minute period.

“It’s hard sometimes because I’m the only caseworker for 110 tenants who live here, but at the same time I love my tenants,” Smoot said. “Certainly, there are folks here with needs who probably belong in a higher level of care, but the resources just aren’t there.”

When a tenant is too much for her to manage, she calls the Behavioral Health Roving Team, a corps of 10 people who provide social work, mental health and medical care.

Krista Gaeta, deputy director of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, which runs the Jefferson, said some clients are too mentally ill to live in the building, which is overseen by the Human Services Agency. She said “a huge number” belong instead in Direct Access to Housing, which serves a higher-need population.

“We don’t have enough services in our buildings,” Gaeta said, “so many of our clients need more, and we’re not doing that heavy substance use counseling. We’re not psychiatrists. We’re not medical professionals.”

Caseworkers at many other housing sites in the Tenderloin juggle dozens of clients at a time, said Mercy Housing’s Christen.

Addressing Mental Illness

This is often the case at units within the city’s Direct Access to Housing program, in which many clients have multiple mental health diagnoses, as well as histories of substance abuse.

Barbara Garcia, director of the Department of Public Health, said at a hearing about homelessness at the Board of Supervisors this year that 32 percent of people who were served in these 2,523 units had experienced more than 10 years of homelessness, and 57 percent had a history of serious mental health problems.

“What’s disturbing to me is that we have a high number of homeless people who have dual- and tri-diagnoses of psychosis, depression and drug and alcohol abuse,” Garcia said. “We have this core group of people who have that, and we see a high mortality rate, and that’s what we’re trying to focus on.”

Christen said she had experienced these problems at homelessness units she helped develop. Staff do their best to manage residents’ ailments, she said, “but it’s often done with bubble gum and tape.”

Rose, the city auditor, concurred that case managers were overworked and underfunded: “Enlisting a fragile population in behavioral health services has strained the city’s network of case managers and mental health workers,” he wrote.

So increasingly the responsibility for determining who gets into housing has rested with the evaluation of the Homeless Outreach Team — social workers and clinicians focused on getting the most vulnerable of the homeless into housing.

“There are a lot of people who are sick,” said Raj Parekh, who ran the team for 10 years as it searched for those whose disabilities impaired their ability to seek help. “When you have a finite amount of services and it does not meet the demands of what you’ve got, you have to triage. We go into the nooks and crannies of the city finding people who are hard to reach.”

While the city does not categorize people in databases on the basis of conditions such as mental health or substance abuse, the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration estimates that roughly 30 percent of the homeless across the United States have behavioral health issues.

In San Francisco, Parekh said, it is much higher. “The overwhelming majority — 85 percent to 90 percent — of people we encounter who are chronically homeless have something deeper going on,” he said. “We’re specifically built to help people who have a hard time getting from place to place on their own, understanding what they need to do, physically having mobility issues, and may have all kinds of substance abuse, mental disorders, cognitive or personality issues that prevent them from connecting the dots themselves.”

Need for Better Records

Staff at the Department of Public Health and the Human Services Agency rarely communicate with each other to coordinate their procedures. One consequence is that clients cannot easily move from one of these tracks to the other based on need. It is hard, for example, to move from Human Services Agency housing to a Department of Public Health building if a physical or psychiatric condition emerges that requires intense supervision. A transfer like that almost never happens.

“There’s so many different departments and different buildings, and that often causes confusion and lack of support,” said Gaeta of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic. “So often we have a tenant with such severe mental health issues who is not doing well in our buildings because we don’t have the level of support to survive. And we don’t want to evict them, but sometimes we don’t know what else to do.”

The messy process of assigning people to housing makes it difficult to assess the value of the city’s multibillion-dollar investment in homeless services in the last decade.

Ben Rosenfield, the city controller, concluded in a 2011 audit of supportive housing that neither the Department of Public Health nor the Human Services Agency had any way to measure the success of their programs.

Both departments, he wrote, “need to collect a variety of tenant outcome data, including data on residents’ length of stay in housing, exits from supportive housing, benefits received, support services used and changes in health and employment status.”

City officials had trouble explaining what happened to all the people who moved into permanent supportive housing but have since moved out.

Some were reunited with family or friends. A few moved to programs with fewer services. Other clients were evicted, and returned to the street or shelters. Some died, others ended up in jail and a few simply disappeared.

“We don’t have good information about why they haven’t succeeded,” said Amanda Fried, deputy director of policy for Dufty’s program at the mayor’s office, called Housing, Opportunity, Partnerships and Engagement. Dufty is most often the first person to whom city departments refer queries regarding the city’s homelessness programs. But even he has trouble getting good data about the success or shortcomings of housing first-programs — a sign of the complexity of the bureaucracy that San Francisco has constructed to battle the problem.

Both Public Health and Human Services officials said privacy rules restricted public access to their client databases. They cited exemptions within the California Public Records Act that restricted records of welfare recipients from being disclosed. They declined to release versions with private details redacted, saying it was impossible to cleanse identifying information.

Limited Resources

A core assumption of the 10-year homelessness plan was that it would achieve financial savings. Not only would the housing-first policy approach improve lives by rescuing people from the streets, but it would also save millions of dollars by reducing emergency medical care.

At the time, the city estimated it was spending a total of $183 million — about $61,000 per person for each of the 3,000 chronically homeless — on emergency room care, treatment in the county jail and other services. Prioritizing housing was expected to reduce these costs to $16,000 per person per year.

It was not until Gavin Newsom took over as mayor in 2004 that the city fully embraced “housing first.” Care Not Cash drastically reduced general assistance and similar monetary payments to the homeless. As of this fall checks of up to $444 were reduced to $62 when clients got a promise of housing.

The difference helped fund permanent supportive housing. The target population was people without a home for at least a year, or who returned to the streets four or more times within three years.

Newsom cited research that stabilizing those with the highest need would save millions of dollars by reducing astronomical hospital bills.

Newsom said he had to make a radical change because the streets were so visibly out of control. “I got really fed up because there’d been an acute increase in people who were dying on the streets,” he said.

The city got financial backing for its supportive housing expansion from the federal Department of Housing and Urban Development and the state Mental Health Services Act, under which the state collects a 1 percent income tax from people earning $1 million a year or more.

Now, the Department of Public Health’s Direct Access to Housing runs 1,539 units at 34 sites, mostly in the Tenderloin. Yet somehow, after a decade of work, the backlog of people eligible for these programs is as long as it has ever been.

“Between Care Not Cash units, Direct Access to Housing units and people waiting in shelters, there’s got to be at the very least 1,000 people on various waiting lists,” said Dufty of the Mayor’s Office of Housing.

While no one is claiming to have “abolished” homelessness, chronic or otherwise, city officials do talk of progress toward expanding supportive housing.

Mayor Lee has said the city succeeded in meeting most of its goals in the 10-year plan, which called for an addition of 3,000 supportive housing units. Since 2004, the city built or leased 2,699 units. Including housing that existed before, the city now has 6,355 units, according to figures in city audits.

While it was a huge feat to get that much built, many of the goals were never realized, said Angela Alioto, who wrote the plan.

Alioto, a former president of San Francisco’s Board of Supervisors, ran a vigorous mayoral campaign against Newsom in the 2003 Democratic primary. When she withdrew from the race, Newsom asked her to orchestrate his battle plan against homelessness.

After Lee became mayor in 2011, he disbanded Alioto’s homelessness planning committee, which met about once a month. Then homelessness appeared to worsen.

“The 10-year plan kind of fell off a cliff,” Alioto said. “The interest wasn’t there.”

Without the 10-year plan, she said, the situation on the streets would have deteriorated faster. Her biggest frustration was that bureaucracy made it hard for clients to get needed services. “It’s so ridiculous to me how many rules and regulations we make homeless people jump through,” she said.

Meanwhile, Lee announced in June that he was recalling the Homeless Outreach Team from its daily rounds and reconstituting the service this fall as a roving street-side medical clinic to head off problems that might otherwise clog emergency rooms. It was not clear whether the team would continue in its primary role of identifying and interviewing candidates for supportive housing.

Newsom had sharp words for his successor, saying that under Lee, homelessness grew while the city failed to provide adequate resources for supportive housing.

“There’s been no accountability,” Newsom said. “The need is more acute than ever. The street population has changed to a degree that so many people are dually diagnosed. So many are suffering from paranoid schizophrenia and self-medicating. And the chronic element is becoming more and more visible, and more difficult for the city to address.”

This special report on homelessness and mental health in San Francisco, in the fall 2014 print edition, was supported in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.

Order the entire full-color, printed version through the website, or become a member and get every edition for the next year.