San Francisco social workers had placed 264 homeless Tenderloin residents in hotel rooms as of Wednesday morning as part of a two-week push to remove most of the neighborhood’s homeless tents. The city initiative comes in the wake of complaints from neighbors, outrage from city supervisors and a May lawsuit against the city by the University of California Hastings College of the Law over deteriorating Tenderloin conditions.

Since the city began placing people in hotel rooms June 10, staff have averaged about 29 hotel placements per weekday. Jeff Kositsky, manager of the Healthy Streets Operations Center, the city’s multi-department homelessness task force leading the initiative, confirmed via text message that the city would not place anyone in hotels Wednesday, adding that he was unavailable for further comment on the city’s progress.

Workers also moved an additional 10 homeless people from street camps into city-sanctioned tent encampments like one at 180 Jones St., a collection of a couple dozen tents surrounded by chain link fencing in the Tenderloin.

“For the folks that they’ve been helping, I think they’re stepping up,” said Devon Tartee, a new resident the city-sanctioned camp at 180 Jones, about the city’s efforts to place people in hotels. Tartee had scheduled a meeting later in the week with a city social worker to discuss long-term housing options in the East Bay, he said.

Since he moved into the camp two weeks ago, people have continued to steal things from his tent like they did when he lived on the street, he said. “It’s pretty much the same” as sleeping outside, Tartee said. “Except I got a gate around me.”

The number of people living on the streets of the Tenderloin exploded after city orders forced homeless shelters to thin their populations and stop accepting new guests at the onset of the pandemic. UC Hastings filed a lawsuit against the city May 4 after the number of tents in the neighborhood grew by 285% from January to late April.

The suit claims that the city neglected both housed and unhoused residents in the neighborhood by allowing tents to choke Tenderloin sidewalks, making social distancing nearly impossible.

On May 6, city officials announced the Tenderloin Neighborhood Plan, an initiative to relocate unhoused people to hotels and sanctioned camps and clean the streets of the neighborhood. In an emailed statement, the Department of Emergency Management said the recent hotel placements were part of that plan.

“Thanks to the joint efforts among the City, community advocates, and service providers, unsheltered San Franciscans are being offered safe sleeping options, which keeps everyone safer during the pandemic,” the statement said.

The city settled with the university June 12, promising, among other things, to remove 70 percent of tents from the Tenderloin and place their owners in 300 hotel rooms by July 20.The Board of Supervisors needs to approve the settlement before it becomes legally binding.

Advocates for the homeless are worried that the settlement, which states that the city will take enforcement measures against unhoused residents who refuse hotel placements, will lead to a return to the city’s pre-pandemic practice of sweeps. Those are instances in which public works staff and police officers issue move-along orders and confiscate unhoused people’s belongings with little to no warning.

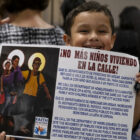

The Coalition on Homelessness and more than a dozen other community organizations held a protest march Tuesday, beginning in front of UC Hastings in the Tenderloin, to highlight societal violence against Black unhoused people and to call out what they feel are inadequate settlement terms.

“The protest was about, basically, pushing back against UC Hastings and calling for real solutions to homelessness and not an enforcement response,” said coalition director Jennifer Friedenbach. “The only thing the settlement added was a zero-tent policy and heavy enforcement.”

Though the city plans to place 300 homeless people in hotel rooms, there are many hundreds more in the neighborhood — and thousands more across the city — who will not receive rooms, she said. Friedenbach fears that if homeless people move into areas where the city has cleared tents, the sweeps will start again, she said.

The recurring tent counts demonstrate the city’s focus on the cosmetics of homelessness rather than the actual people living inside the tents, Friedenbach added.

“Tents do not have heartbeats; they do not have blood flowing through their veins; they do not have brothers and sisters and parents,” she said. “What we care about is the human being that is either inside of that tent or outside of that tent.”

Rhiannon Bailard, executive director of operations at UC Hastings, said university administrators were so far satisfied with the city’s progress in the Tenderloin and that the city staff had done well to respect the rights of unhoused neighbors with minimal police presence during the initiative.

“I would point out that no one has seen anything to indicate the police are involved,” Bailard said. She added that, while the Tuesday protest highlighted the plight of Black unhoused people, little credence had been paid to the neighborhood’s housed residents of color, some of whom hadn’t left their apartments since hundreds of additional unhoused residents began living in the area.

“Sixty percent of the residents of the Tenderloin are people of color and for way too long, this is a community that has been disregarded,” Bailard said.