When the city’s landmark universal health-care program started serving uninsured residents in 2007, its users were spread throughout the city and most spoke English as their primary language.

Since the federal program known as Obamacare came into force three years later, those demographics shifted dramatically, as tens of thousands of residents have been moved on to Medi-Cal or Covered California, a new city report shows. Today, the city program, Healthy San Francisco, predominantly serves Spanish speakers and people living in the city’s southeast neighborhoods, where poverty is high and educational attainment low — and where undocumented immigrants are concentrated.

Because Healthy San Francisco also covers noncitizens, the Department of Public Health might have the names of hundreds or thousands of people who are in the country illegally. And that list could be of special interest to the fledgling administration of Donald Trump, which has already made moves to ramp up deportation efforts.

If pressed, however, city officials say they would refuse to surrender those names to the federal government.

“We can’t envision a scenario where we would turn over those records, given medical privacy laws,” said John Coté, communications director for the City Attorney’s Office.

Information about Healthy San Francisco’s participants is entirely under San Francisco’s control, since the program receives no federal dollars, he said.

Overall, the city receives more than $1 billion in federal funding, which could conceivably be at risk if the Trump administration targeted San Francisco and other so-called sanctuary cities that shield undocumented immigrants.

Healthy San Francisco covers people who cannot afford or qualify for care under the state Medi-Cal program or the Covered California insurance marketplace, and has always been accessible regardless of employment or immigration status. It was those especially vulnerable populations who remained in the local clinic-based system.

The Department of Public Health operates the city program, which offers most services for free to low-income residents through a network of dozens of city-run and nonprofit health centers. It retains addresses for all current and previous participants, but it does not record anyone’s immigration status. But if the Trump administration managed to access the data, it would not be able to discern which residents were here illegally, said Colleen Chawla, the health department’s director of policy and planning.

The city’s ability to safeguard sensitive personal information will soon be a focus of the new Federal Select Committee of the Board of Supervisors, said Chelsea Boilard, legislative aide to District 1 Supervisor Sandra Lee Fewer, who sits on the committee. The panel will assess which city policies could face attack from the White House and design strategies for responding.

“The conversations are just beginning,” Boilard said. “This issue is definitely a priority.”

Falling Enrollment

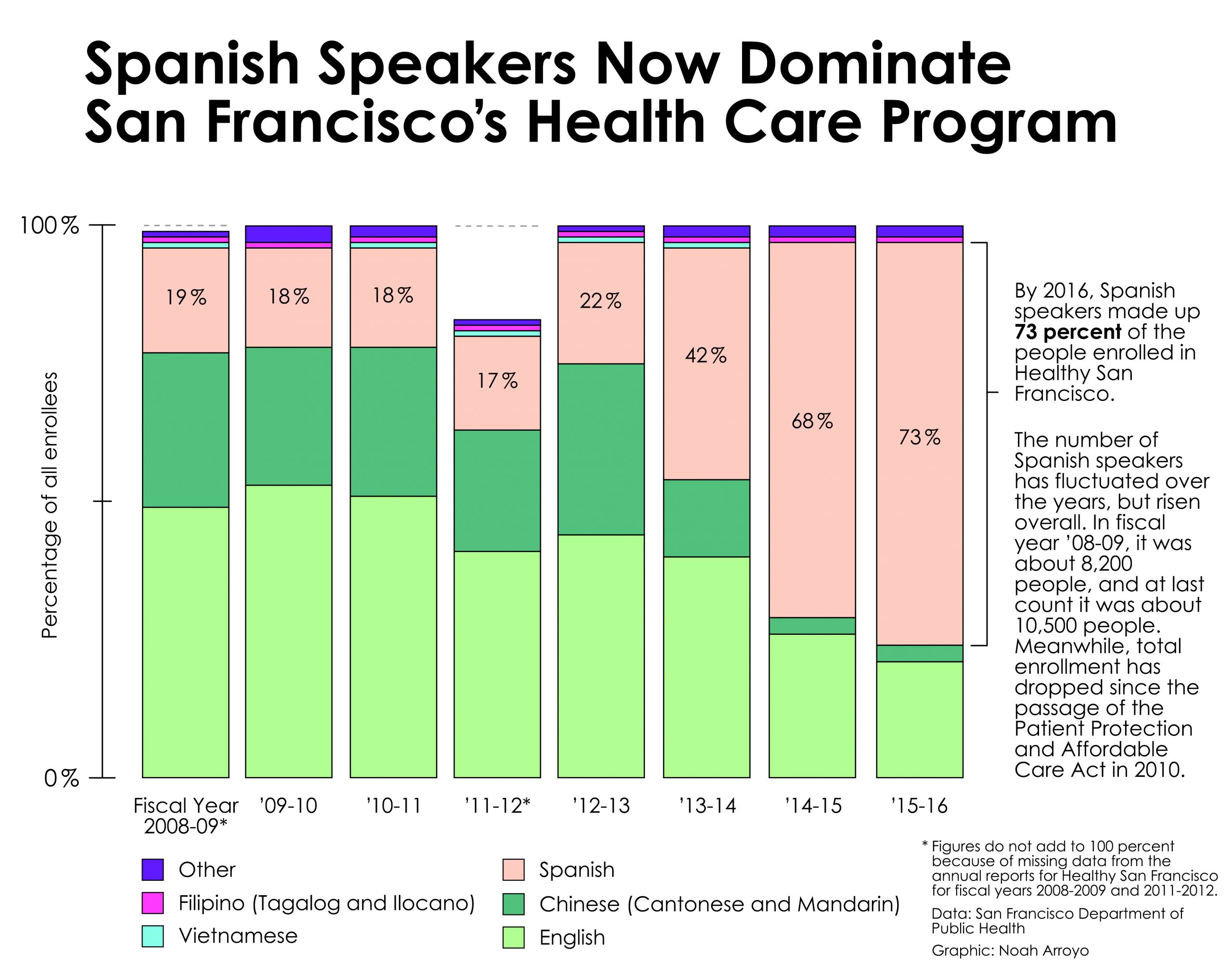

After Healthy San Francisco’s 2007 launch, enrollment rose quickly, and peaked at 54,348 participants in the 2010-2011 fiscal year. But people began dropping off after Obamacare — the federal Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act — was enacted in 2010.

After federal health reform picked up speed, most enrollees remaining in Healthy San Francisco were those who did not qualify for Medi-Cal or could not afford health insurance through the exchange, or who could not qualify because they were not legal residents.

As Healthy San Francisco’s numbers dwindled, the health department estimated that enrollment would ultimately stabilize at 18,000 to 19,000 people, and that 17,000 of them would be undocumented immigrants, the San Francisco Chronicle reported in 2013, citing department estimates.

Asked about those figures in late January, Chawla told the Public Press in an email: “I don’t know where that estimate came from but I would not want to guess at the legal status of the remaining HSF members.”

She said language and other demographic information might be “proxy measures” for characterizing how many participants are undocumented.

At peak enrollment, about half of all users spoke English. Cantonese and Mandarin speakers together constituted the next-largest group, followed by Spanish speakers. When enrollment declined, Spanish speakers became the dominant group.

By the end of fiscal year 2015-2016, enrollment had dropped to 14,404, with 73 percent primarily speaking Spanish, 21 percent English and 3 percent Cantonese or Mandarin. Citywide, by comparison, just 12 percent of residents speak Spanish, and 18 percent Cantonese or Mandarin, according to the health department’s 2016 Community Health Needs Assessment.

Remaining Healthy San Francisco users now cluster in the city’s southeast.

At peak enrollment, 46 percent lived in five eastern San Francisco neighborhoods: Mission, Excelsior, Visitacion Valley, Bayview-Hunters Point and the Tenderloin. But by 2016, those neighborhoods accounted for 91 percent of participants.

Undocumented immigrants appear to live in higher proportions in those neighborhoods as well, according to 2013 citywide data analyzed by the Public Policy Institute of California.

The data, broken down by ZIP code, showed that the highest density of undocumented immigrants was in 94110, which contains most of the Mission and Bernal Heights neighborhoods. High concentrations live in those other southeast neighborhoods, as well as on Treasure Island. The ZIP code 94102, spanning Hayes Valley and the Tenderloin, also has large estimated migrant populations.

Several of the neighborhoods are marked by extreme poverty and low educational attainment, according to the city’s fiscal 2015-2016 report about Healthy San Francisco. For example, at least 25 percent of residents live below the federal poverty level ($12,060 for a single-person household) and have not completed high school in Bayview-Hunters Point, Visitacion Valley, Hayes Valley, Chinatown, the Tenderloin, South of Market and the Mission District.

Federal Chaos Prompts Response

On Jan. 25, Trump signed an executive order to build a wall along the U.S.-Mexico border, and to encourage federal and local law enforcement to work together to detain and deport undocumented immigrants accused of crimes.

District 11 Supervisor Ahsha Safai, a first-generation Iranian-American who represents the Excelsior and Outer Mission neighborhoods, called it “a sad day in our nation’s history.”

“We have a tyrant and a fanatical person who has pretty much taken over the presidency,” he said. “He’s targeting anyone he feels can be easily scapegoated.”

Referring to the city’s undocumented population, Safai said that “about 99.9 percent of the people are law abiding and, frankly, doing work that not a lot of people want to do.” He expressed confidence that the Department of Public Health would protect personal information about Healthy San Francisco’s users.

Trump issued another executive order, on Jan. 27, that called for barring Syrian refugees from entering the United States; blocking all other refugees for 120 days; and prohibiting citizens from seven Muslim-majority countries from entering for 90 days. On Friday a federal judge in Seattle suspended the order’s enforcement nationwide.

On Tuesday the Ninth U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals in San Francisco heard arguments in the case of State of Washington & State of Minnesota v. Trump, in which Washington’s solicitor general argued that the travel bans were beyond the scope of the president’s constitutional and statutory authority. A lawyer for the Justice Department countered by saying that the courts should not second-guess the president’s decisions regarding national security. The court said Wednesday that it would not issue a ruling by the end of the day. Regardless of the appellate court’s decision, the case is expected to end up at the U.S. Supreme Court.

In the days before the travel bans were suspended, the immigration system was thrown into chaos as travelers were detained or sent back upon arriving, spurring protests at major U.S. airports, including San Francisco International.

San Francisco officials felt compelled to respond to the tense, unpredictable political upheaval.

The same day that Trump issued the bans, the city’s Department of Public Health emailed all staff and workers at local nonprofits to reassure them after Immigration and Customs Enforcement agents visited the Good Samaritan Family Resource Center in the Mission in search of a convicted sex offender facing deportation, the San Francisco Examiner reported.

“This brief visit by ICE sounds an alarm for many members of our community,” wrote Barbara Garcia, the health department’s director. “We are working with community organizations, the Mayor’s office and other city agencies to ensure that all San Franciscans, including immigrants, continue to access services in their communities. We are consulting with the City Attorney to make sure we have the strongest legal advice moving forward.”

Other city agencies quickly followed suit. The following weekend, the San Francisco Unified School District sent out an automated phone call to parents to try to assure them that their children would not be vulnerable to prying immigration agents.

“There are existing laws that help keep your children safe while in school, regardless of their immigration status, and SFUSD staff will not cooperate with any official seeking information about your child unless they have a court order,” the message said.

In his State of the City Address on Jan. 26, Mayor Ed Lee promised that San Francisco would remain a sanctuary city and not assist the federal government’s enforcement of immigration laws, unless compelled by specific laws or court orders.

City Attorney Dennis Herrera sued the Trump administration on Jan. 31 over an executive order that threatened to withhold federal funding to sanctuary cities.

In a press release explaining the lawsuit, Herrera’s office said City Hall receives about $1.2 billion a year in federal funding across a broad array of programs.

“The president’s executive order is not only unconstitutional, it’s un-American,” Herrera said. “That is why we must stand up and oppose it. We are a nation of immigrants and a land of laws.”

The mayor added his support in a separate statement.

“Let today’s lawsuit be a reminder to the nation that San Francisco is a city that fights for what is right,” Lee said. “We will not waver in our commitment to protect our residents.”