It’s being built in China.

It’s taken twice as long as expected.

And it will cost double what you’ve been told.//

When completed, the new east span of the San Francisco-Oakland Bay Bridge will be not only the most complex engineering feat in California history, but also the most expensive, with a cost never subjected to public scrutiny.

Although today’s price tag stands at $6.3 billion, the figure accounts for only salaries and hard materials—things like concrete and steel and cranes. When all is said and done, the new Bay Bridge will wind up costing tax- and toll-payers more than $12 billion—a figure that leaves even the officials in charge “staggered.”

Much of the difference comes from interest and other financing charges—money that commuters will be paying off until at least 2049. Little attention has been paid to billions of dollars not included in the direct construction cost projections published in glossy public reports.

Why the price has skyrocketed is a tale of politics, bureaucratic bumbling, and unforeseen construction problems—all classic ingredients of California public works projects. It is a tale of obscure but powerful agencies, legislative bickering, and four successive governors grappling with a project so massive and complex that one consultant suggested the human mind might be unable to grasp, or accept, “the magnitude of the undertaking and the time and resources required to complete it.”

While public attention is focused on something new and grand, replacing the aging and increasingly unreliable existing east span with an iconic edifice that will define the San Francisco Bay into the next century, it is easy to overlook other aspects of the Bay Bridge project that contribute to spiraling costs. Caltrans officials are expected to announce this week that problems in Asia, where the majority of the bridge is being manufactured, will push those costs even higher. Among those are problems with fabrication and shipping of critical steel components in China that could add $100 million or more to the final price tag, and international bickering over design drawings and blueprints that could ultimately cost tens of millions more.

It is impossible at this point to account for every dollar spent on the Bay Bridge project so far. While nearly $500 million has been paid for seismic retrofitting of the west span and construction of a new west approach—work already completed—bills continue to roll in for the east span which is expected to take until 2013 to complete. Public records show that through September, $3.8 billion in expenses have been incurred on the east span construction and at least $1.9 billion more in expenses are expected soon.

Since 2005, when the state auditor completed the last examination of Bay Bridge spending requested by the Legislature, there has been no independent fiscal oversight of the project. What audits there have been are internal examinations conducted by the various agencies involved in managing the project.

CHIP IN FOR THIS REPORT ON SPOT.US |

Still, while it will be years before a final accounting is made, Brian Mayhew, the chief financial officer for the Bay Area Toll Authority—which allots money for the project—insists that audits of the Caltrans payment process are conducted every two years and if there is anything amiss, it will amount to honest mistakes.

“Caltrans is a big bureaucracy and they’re very complex to deal with, but they’re not fraudulent,” Mayhew said. “They’re not stealing money. The risks involved with Caltrans are mostly accounting errors,” using money for the wrong project or over-assessing overhead and other expenses. Categorized as “capital outlay support,” by September, $771.9 million had been spent on Caltrans overhead and other support costs, and that is expected to rise to $1.2 billion by the end of the project.

Some of the most expensive overhead involves keeping qualified Caltrans engineers and contractors on the ground overseas to ensure bridge components can stand the test of time and the next big earthquake. Much of the steel fabrication and know-how for the self-anchored suspension span—the project’s crown jewel—has been outsourced to at least seven countries: Canada, China, England, Japan, Norway, South Korea and Taiwan. In previous eras it would seem inconceivable that the major steel components for such a project would be built in China, but that is exactly what is happening.

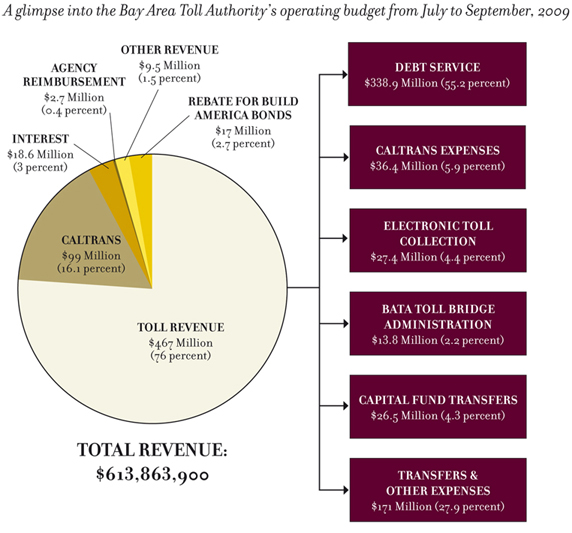

WHERE YOUR TOLL DOLLARS GO

Randy Rentschler, director of legislation and public affairs for the Metropolitan Transportation Commission, the Bay Area’s lead transit planning agency, said the extensive foreign involvement is simply because “we’re just not doing anything anymore as a country.”

After the last of America’s great building booms, when the expansive federal highway system was constructed in the 1950s, a growing disdain for big government took the wind out of politically mandated public works projects.

This project has outlived many a political career, including those of San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown and Governor Gray Davis, and countless other legislators from the Bay Area and in Sacramento. Most of the officials who green-lit the project are long gone, and the lack of continuity in state and local leadership represents a challenge all its own. There aren’t many lawmakers in Sacramento with a long history in their current positions, and fewer who know much about the Bay Bridge.

This lack of governmental memory on such a marathon construction project—combined with knowledge that many costs can be pushed far into the future—and coupled with overly optimistic cost estimates, helps to explain why the stated price of construction has grown nearly fivefold, from the $1.3 billion estimated in 1996 to more than $6.3 billion today. When finance charges are taken into account, the actual cost paid for the construction and financing of the bridge, when it is paid off in 2049, will be more than $12 billion. That is almost twice what any state agency has previously acknowledged.

Yet when reached at his office Friday, Brian Mayhew, the chief financial officer of the Bay Area Toll Authority (BATA), which raises revenue for the bridges, said that officials have long known the bridge would cost roughly twice direct spending when including interest.

“The usual rubric we use is you take the principal and you just about double it for principal and interest,” he said. “We’ve got very low-cost money, so we really feel very good about that fact. But it’s true, interest is just the price of borrowing money.” Mayhew added that the full cost of the Bay Bridge is not a subject he often discusses publicly. “I’ve discussed it at the board a couple of times,” he said. “My boss is staggered by it. I don’t think we’re hiding it. Just no one has ever asked before.”

BEATING THE NEXT BIG ONE

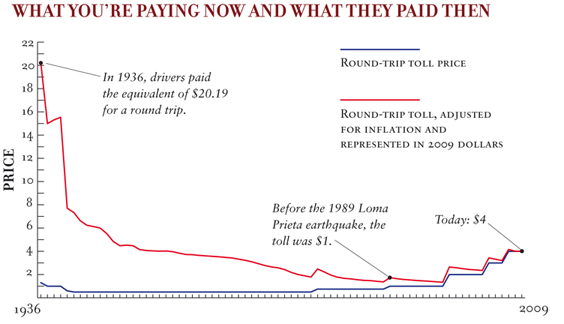

Few people refer to the Bay Bridge by its proper name: the James Rolph Bridge, named for the longest-serving San Francisco mayor, who went on to become California governor at the height of the Great Depression in 1931. “Sunny Jim,” as he was known, died during his first term as governor, before he could see his dream of the first bay crossing realized. The span opened to traffic in 1936, after three years of construction that cost $77 million.

For the next half a century, millions of commuters took the bridge for granted, navigating its 4.5 miles between Oakland and San Francisco. That all changed in 1989, when the magnitude-6.9 Loma Prieta earthquake collapsed a section of the east span and disrupted commuting patterns for a month.

//Mayhew added that the full cost of the Bay Bridge is not a subject he often discusses publicly. “I don’t think we’re hiding it. Just no one has ever asked before.”//

But the temblor did more than simply unseat a critical section of the Bay Bridge and pulverize other portions of the Bay Area transportation infrastructure. It sounded alarm bells in the halls of state government and triggered a shockwave of spending that continues to this day.

San Francisco has a reputation for rebuilding in the wake of disaster, from the early frontier days of the Barbary Coast to the 1906 earthquake and the quick rebuilding of the Marina District in 1989. When the forces of nature render reality utterly unrecognizable, there is always the opportunity to start anew.

When the Loma Prieta dust settled, engineers took a look at the east span, igniting a debate that in typical California fashion lasted for years, about whether to seismically retrofit the structure or to replace it with something new and grand.

In 1990, Caltrans contracted with Abolhassan Astaneh, a professor of civil engineering at the University of California Berkeley, to conduct a study. The three-year study concluded that a retrofit would be safe and would make fiscal sense. Then, in 1994, the Northridge earthquake damaged a retrofitted bridge near Los Angeles. This prompted Caltrans to again consider the replacement option for the east span of the Bay Bridge. Over the next few years, both options were weighed simultaneously. In 1996, Caltrans estimated that it would cost $1.3 billion to retrofit the existing structure. The agency also concluded that for a few hundred million more, an entirely new east span could be constructed. This would have a longer lifetime and would require less maintenance.

A decision to replace the span percolated its way up from the depths of Caltrans to the desk of the secretary of Business, Transportation, and Housing—essentially Caltrans’ boss—who recognized a replacement project would need gubernatorial and presidential support to wade through the muck of environmental studies, permits, and financing.

Citing time, safety, and cost, then-Gov. Pete Wilson recommended a “skyway” design—a graceful term for a freeway on stilts such as the Antioch Bridge that spans the San Joaquin River connecting eastern Contra Costa County to Sacramento County. Bay Area leaders pushed back, calling for a more singular design, one to rival the Golden Gate Bridge.

There was one catch. If the Bay Area wanted a signature design, they would have to chip in for the cost. Originally, a mixture of state and federal funds would have footed the bill for a simple and less expensive design (the skyway was estimated at $1.5 billion). A more elaborate design was then estimated to cost $1.7 billion. In retrospect, Rentschler said, there was no doubt which option the politicians would push for.

“There was just no way that the Bay Area wasn’t going to do something special on the bay—there was just no two ways about it,” he said, particularly when you considered that the difference in cost estimates at the time was just $200 million, or about 18 months worth of tolls. “Of course we’d say yes to that,” Rentschler said.

“Every time we touch the bay, it has to be improved,” he said. “We’re going to have an internationally recognized piece of sculpture on the bay that’s functional and that’s absolutely in tune with what the Bay Area has been doing since the 1930s,” when both the Bay Bridge and the Golden Gate Bridge debuted.

So a lengthy process of proposals and designs began, with the MTC at the center. Everyone, it seemed, had a vision of what that sculpture could be, with the design panel deliberations often resembling a circus during the 16-month selection process.

Though the initial estimate for a signature span was $1.7 billion, there was much political bickering, agency dysfunction, and bureaucratic snafus to come, and all the while, the bridge’s price tag would spiral ever-upward.

LOOKING FOR CASH UNDER EVERY ROCK

From the moment in 1997 when Governor Wilson finally announced his support for Caltrans’ plan to replace the east span, the Bay Bridge took center stage in a Sacramento political drama that has yet to see its final curtain—or price tag. Just a year earlier, in 1996, voters had approved the sale of $2 billion in bonds to pay for the seismic retrofit of state-owned highways and bridges. Yet only $650 million of that was earmarked for the rehabilitation of all toll bridges in the state, including the Bay Bridge. So Wilson’s decision to replace the east span, a decision made after voters had approved funding that did not include the replacement project, had the makings of a budget-buster.

Recognizing a financial crisis in the making, lawmakers began scouring nooks and crannies of the state treasury, looking for ways to pay for a project they believed would only continue to increase in price.

Quentin Kopp, then a state senator from San Francisco, quickly introduced two bills in December 1996 providing $2.6 billion in funding specifically for retrofitting or replacing seven of the state’s nine toll bridges—five bridges in the Bay Area and two in Southern California.

Kopp’s bill was followed by more than seven years of heated debates between Bay Area legislators and their counterparts statewide, who believed that if the region wanted a new bridge, its own residents should pick up the tab.

Kopp, now a retired San Mateo County Superior Court judge and board member of the California High Speed Rail Authority, lays the blame for the protracted political bickering and subsequent cost increases squarely on Caltrans.

“The Bay Bridge is part of the state highway system and the cost should be paid from state highway funds,” he said recently. “It started with Caltrans. These cost overruns evolve from Caltrans’ performance and its original negligent cost estimate.”

“It’s not Caltrans’ fault that the bridge was delayed and the costs went up,” MTC’s Rentschler said. “Caltrans’ role in this is often misunderstood. Caltrans is an organization that is going to do what the governor and his administration tells them to do.

It was really the administration that was using this as a way to try to deal with the budget problem,” he said. “It wasn’t ever a design problem.”

Ultimately the dispute over who would pay for the construction of a new, aesthetically enhanced bridge led to a compromise between Wilson and Bay Area lawmakers providing that costs would be split between state and local funding, with a third of the money derived from bridge tolls.

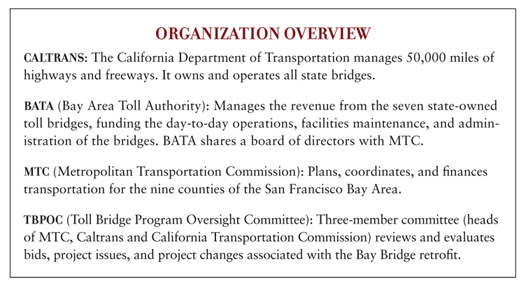

Kopp’s legislation, along with two other Senate bills, also added additional elements of Bay Area control over bridge design and spending. The legislation designated the Metropolitan Transportation Commission the stewards of the bridge design selection process, and it created the Bay Area Toll Authority as an independent subsidiary agency of the MTC. The Bay Area Toll Authority (BATA) would be charged with managing toll collections and financing the multibillion-dollar Bay Area seismic retrofitting program.

Thus BATA, an obscure agency that few taxpayers even knew about, and the MTC emerged as the nexus of power in overseeing everything from accounting for toll collections to design and construction activities.

THE WILLIE FACTOR

The origins of the current design are murkier than one would expect for such a high-profile project. Between May 1997 and June 1998, designs volleyed back and forth between a cluster of advisory panels and decision-making bodies at both the MTC and Caltrans before a design resembling the current plan appeared.

It started with the MTC’s engineering design advisory panel—a 34-member collection of engineers, architects and academics chosen by the MTC to inform its design task force, which in turn advised the MTC’s decision-makers. In May 1997, the panel whittled down 13 submissions to two options for further study: a cable-stayed option and a self-anchored suspension option.

Eventually the self-anchored suspension option, though very complicated and difficult to build, was deemed the winner. The MTC commissioners approved the choice by an 11-1 vote.

Caltrans then hired T.Y. Lin International to complete the design, to the tune of $81 million. In another five months, by May 1998, T.Y. Lin and Caltrans presented the MTC with a rough working design for the self-anchored span.

That’s when real political trouble began to brew. When he saw the design for the new bridge, San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown sought to block its construction. He claimed that its alignment would interfere with his plans to develop Treasure Island, a manmade island located adjacent to Yerba Buena Island that had been bestowed on the city by the U.S. Navy after closure of its base there. Brown had recently unveiled a $12 million development plan for Treasure Island, which envisioned a casino, marina and resort. At Brown’s urging, the Navy refused Caltrans access to the islands to conduct soil testing for mandatory environmental studies. This delayed the project two years and added millions to the cost.

Brown’s action didn’t set well with his East Bay neighbor. From Oakland’s perspective, much hinged on the visual appeal of a landmark bridge. The east span of the Bay Bridge had long been the ugly stepsister of other Bay Area bridges, particularly the Golden Gate. With a new design for the east span, Oakland and the East Bay could potentially have an iconic and world-renowned structure.

Mayor Brown’s interference created acrimony on both sides of the bay, and the dispute reverberated all the way up to the White House. In December 1999, the new governor, Gray Davis, appealed to Washington to intervene in Caltrans’ struggle with the Navy. The California Transportation Commission, a 13-member board responsible for allocating funds for highway, passenger rail and other transportation improvements throughout the state, sent a strongly worded letter to the Navy in April 2000 suggesting that it was “jeopardizing safety by obstructing progress.”

//The announcement of drastically increased costs sent shockwaves through the Capitol and resulted in calls for audits of Caltrans.//

A study released by the Army Corps of Engineers a few weeks later effectively ended Willie Brown’s central and costly role in the saga, when it found that realigning the bridge to suit Brown’s plans would potentially add tens of millions to the cost and delay the project by another 15 months.

During this squabbling, construction cost projections were rising rapidly. Caltrans, which retained responsibility for managing toll bridge construction, shocked lawmakers in 2001 by revealing the bridge would now cost $2.6 billion.

The Legislature responded by providing $5.1 billion in funding for all of the state-owned toll bridges, including a $448 million contingency fund, money set aside for extraordinary circumstances or unforeseen expenses. Lawmakers believed the additional funding could be obtained through a mixture of federal highway bridge funds and a projected $2.8 billion in toll bridge revenues, generated by extending for up to 30 years the $1 seismic surcharge on tolls that had been in place since 1998.

THE BEGINNINGS OF MORE BEGINNINGS

On a sunny day in January 2002, with political bickering over the bridge quieted to a murmur, Gov. Gray Davis stood on Treasure Island against the backdrop of the existing bridge—undeterred by the presence of a small group of protesters concerned with the new design’s seismic safety. He was there to preside over the groundbreaking ceremony for the eastern span—six years after voters had initially approved money for seismic retrofitting of California toll bridges—where he congratulated Caltrans and legislators for crossing the aisle to get to this celebratory moment, which culminated in a fireboat water display under the existing bridge.

At the ceremony, Davis proudly predicted the new bridge would be open to traffic by 2007.

But the design for the signature portion of the bridge had not yet been finalized. No bids had been made by contractors. Planners had agreed, though, that the first portion of the bridge, starting in Oakland, would be built the same way regardless of what signature design was chosen. Thus groundbreaking was possible in a limited way, though the construction of the most difficult portions of the bridge would be years, and countless political squabbles, away.

In March 2004, Bay Area voters approved Regional Measure 2, authorizing the use of toll revenues not only for bridges, but mass transit and highway improvements as well, and in the process authorized increasing the automobile toll on all Bay Area bridges by $1. Voters also gave BATA authority to impose future toll increases to meet financing obligations—but only with prior legislative approval.

Yet barely a month after Regional Measure 2 was approved, an independent review committee warned that costs for the Bay Bridge’s self-anchored suspension span would be higher than anticipated. The committee was correct: When bids were invited that May, just one bidder—a joint venture of American Bridge, Nippon Steel and Fluor Corporation—submitted a bid for constructing the self-anchored suspension portion of the east span. The cost: $1.8 billion if American steel was used and $1.4 billion with foreign steel.

In August 2004, Caltrans finally revealed that, due to time delays and rising prices, its entire Bay Area toll bridge seismic retrofit program—including the replacement of the east span—would cost $8.3 billion, up from its previous estimate, in 2001, of $5.1 billion. East span replacement costs alone would exceed $5 billion, leaving that specific project at least $3 billion under-funded. This overrun was far more than could be covered with the meager $448 million contingency fund created in 2001.

While Caltrans was in the legislative hot seat, it wasn’t acting alone—it was the MTC and its design task force that had selected the ambitious design. Caltrans turned to the MTC to help investigate cost overruns, and Bechtel Infrastructure Corporation—the San Francisco-based construction and consulting firm— was retained to independently review the self-anchored suspension bid and study the cost and time implications of rebidding it, scrapping the design or awarding the pending bid.

Among other things, the Bechtel study concluded that if Caltrans rebid the self-anchored suspension contract, it could expect up to $200 million in additional costs. Bechtel told Caltrans that “if achieving seismic safety for the motoring public is the primary objective, awarding the current bid is the most effective option.” It was this report that was the basis of Caltrans’ bad news to the Legislature.

Although legislators scrambled to draft an interim solution for the funding shortfall, a bill drafted to solve the problem died on the desk of California’s new governor, Arnold Schwarzenegger. The continuing lack of funds saw the sole self-anchored suspension bid expire because Caltrans had not yet authorized construction to commence within the required time frame, forcing the agency to reconsider its options.

The announcement of drastically increased costs sent shockwaves through the Capitol and resulted in calls for audits of Caltrans, and reopened the debate within the administration about building the simpler skyway design. But just as the feuding among Caltrans, the MTC and the governor over skyway versus suspension span reached a boil, in November 2004 Schwarzenegger made a new appointment to the top post at Caltrans. He chose Will Kempton, a Silicon Valley transportation executive who had begun his transportation career with Caltrans in 1973 but at the time of his appointment was working for the city of Folsom, near Sacramento.

Kempton, who stepped down last July for a higher-paying position with the Orange County Transportation Authority, backed the existing self-anchored suspension plan, even though it was associated with risks such as time delays and increased costs.

As rumors of reverting back to a skyway design circulated, internal documents supporting the skyway option were distributed among staff members at the state Business Transportation and Housing Agency, an arm of state government that encompasses 14 departments, including Caltrans. These documents were provided to us by Sunne Wright McPeak, then Secretary of Business, Transportation, and Housing, and now president and CEO of the California Emerging Technology Fund. In the documents, the simpler bridge design was justified by citing cost savings of up to $400 million and more certainty in constructing “a safe bridge at a reasonable cost by 2012.”

“After 15 years of delay, controversy and political infighting, the Schwarzenegger Administration has taken just 15 months to rigorously review the entire project and offer a timely and cost-effective solution,” the documents read. “The State’s priority is to build a safe bridge at a reasonable cost in the shortest amount of time. The skyway provides the best option—and the least risk—for the bridge to be completed on time and within budget.”

It was the MTC’s Steve Heminger, the agency’s executive director, who was keen to point out that scrapping the design, which was already nearing completion by T.Y. Lin and Moffat Nichol, could cost $50 million per year in delays. “Steve was probably the most listened-to voice, the most powerful and the most credible,” McPeak said in a recent e-mail.

However, the more ambitious design also posed the risk of increased cost because it was untested. When the self-anchored suspension span was originally put out to bid in 2004, McPeak said potential bidders posed almost 900 questions on the bid documents. “That is a pretty damn good sign that you have a problem with the design,” she said.

Nonetheless, in a January 2005 letter to Caltrans, one contractor, C.C. Myers, presented an unusual compromise, arguing in favor of a skyway design. They explained that this design would be far cheaper to build, and that a tower could be added that would look much like the self-anchored span, without the same functional purpose.

“Towers and cables can be added for the appearance of a self-anchored span to present a contract that is much less complex, faster to build, and at a fraction of the cost of the current design,” the letter from C.C. Myers said. “Given the current fiscal state of California, we all need to adopt a ‘function over form’ mentality, and see to it that our coffers are not needlessly emptied on what is little more than an architectural pipe dream.”

Ultimately, a national consulting firm, The Results Group, was commissioned to review Caltrans’ cost estimates for the Bay Bridge east span. The consultant reported in January 2005 that cost estimates for the east span had ballooned to $5.3 billion from the $1.7 billion originally projected in 1997. These findings were reported to the Legislature later that year.

//The ambitious, untested design raised almost 900 questions from bidders. “That is a pretty damn good sign that you have a problem with the design,” one official said.//

The report identified several factors contributing to the rising price tag, including steel fabrication, “contractor mobilization,” “capital outlay support” costs, insufficient contingency funds—and the fact that initially there was just a single bidder. The report concluded that despite Caltrans’ best efforts to produce accurate cost projections, those estimates repeatedly fell short, in part because Caltrans had never before engaged in a project of this magnitude.

“The east span is at least three times more costly than any project ever built by Caltrans before,” the report concluded. And when the self-anchored suspension design was selected in 1998, “none of the parties—from state government to local entities to the public—fully comprehended the cost implications of the enormity of this project, in particular the complexity of the suspension span. This project is not unlike most mega-projects around the world in suffering cost increases and schedule extensions.”

One of Caltrans’ lead project engineers, Tony Anziano, recently said that the complexity of the project was dismissed in favor of aesthetic considerations when it came time for the MTC task force to select a design. “They understood it. And they wanted it,” Anziano said in a recent interview. “They were looking for an icon.”

Rentschler suggested that the bridge ultimately became a pawn in a regional battle over who exactly would pay for the construction. “The design problem entered into it as leverage over the Bay Area to get us to put more money up. The rank and file, the real Caltrans individuals, are victims of a crossfire that took place between the political interests of the Bay Area and the financial interests.”

A CHANGE IN COMMAND

With mistrust of Caltrans reaching an apex and a growing legislative reluctance to give the department complete authority over construction of a bridge with a rubber price tag, frazzled lawmakers finally responded with decisive action in 2005 by passing Assembly Bill 144. The bill dictated a budget for the Bay Bridge project, gave BATA expanded management and financing responsibility, and created a new three-person entity with enormous budgetary power, the Toll Bridge Program Oversight Committee (TBPOC). The law also imposed yet another $1 toll increase, the second so-called “seismic dollar,” to begin Jan. 1, 2007.

Meanwhile, Caltrans was forced to rebid the east span because no contract had been awarded within the required time period. The second time around, to encourage more competition, Caltrans split the project into segments that were bid separately. Caltrans also sought to sidestep federal requirements that would necessitate the use of domestic steel on such a project. Under the so-called “Buy America” requirements for federal contracts, all manufacturing processes for steel and iron material used must occur in the United States. If, however, the bidder demonstrates that no American supplier can provide the same product or services within 25 percent of the foreign cost, then the foreign bid is acceptable. But the building of the bridge in the United States would cost far more than in China, and given the already-escalating costs, adhering to the federal requirements was not an option. So Caltrans chose to eschew federal money.

When the contract was put back out to bid in 2006, it was the result of years’ worth of bidder outreach meetings and numerous amendments to the bid package, including the “defederalization” of the self-anchored suspension contract. By foregoing federal money for the suspension contract, potential bidders were no longer required to submit two bids. The change also meant that bids were more likely to get started right away, because factories big enough to construct the Bay Bridge components were hard to come by in the United States. Were an American fabricator bundled in the winning bid package, it is likely that an entirely new facility would have needed to be built before work could begin.

“No one would have been happier than we if we had had this bridge fabricated in the United States,” Heminger said. “But we also have an obligation to the taxpayer that we spend their money wisely. And I think it says more about the state of the American steel industry than it says about China or Japan.”

Yet even before rebidding commenced, the project was grossly behind schedule, with Caltrans expecting completion of the east span by 2013, four years later than its earlier estimates. According to a subsequent report by the state auditor, an entire year of delay was caused by Caltrans postponing the self-anchored suspension bid invitation five times to add various contract requirements, prompted by a string of requests from bidders for clarifications. Caltrans’ protracted process alone increased basic overhead and administrative costs by more than $200 million.

AN OBSCURE COMMITTEE WITH VAST POWERS

Although existing law requires Caltrans to make regular reports to the Legislature, traditionally years would pass with no word from the department until suddenly Caltrans would reveal that it was over budget and in need of additional state financing.

This was a situation that was ripe for scapegoating, said Stephen Maller, deputy executive director of the California Transportation Commission, a member of the project management team that does legwork for the Toll Bridge Program Oversight Committee. The Legislature could point to Caltrans and “call it dysfunction junction.”

The creation of the TBPOC was the Legislature’s solution to problems with management and accountability on Bay Area toll bridge projects. Since the TBPOC grabbed the management reins, officials say more information is collected and reported on an ongoing basis. Heminger said the quarterly reports produced by the TBPOC keep the state Legislature and the public abreast of project developments, risks, and accomplishments.

Instead of having Caltrans act alone, these project management decisions have been made by the three-member TBPOC, consisting of Heminger from the MTC, California Transportation Commission chairwoman Bimla Rhinehart, and Caltrans Director Randy Iwasaki.

While legislators mandated specific responsibilities to the committee, such as review of construction change orders, the law creating it was written so broadly that it could be interpreted as giving the committee considerable control over all aspects of the Bay Area toll bridge seismic retrofitting and replacement program, subject to approval by yet another body, called the BATA Oversight Committee, which meets monthly. The TBPOC has a staff of fewer than a dozen and operates on an annual budget of $550,000.

When the TBPOC was created, it restructured the entire construction management process to take much of the power away from Caltrans.

The way the law was written also put BATA on the hook in the event that funding proved insufficient. In contrast to the prior statutes, it didn’t just put a number in the state law for a cost and then divide the responsibility between the Bay Area and the state, but it also included the $900 million uncommitted contingency, which Heminger said “was an admission that we didn’t know everything and there were unexpected things that would pop up with cost consequences.”

Most TBPOC sessions involve construction change orders—requests from contractors for additional money for unexpected increases in the cost of materials or labor. According to committee meeting minutes obtained under the state’s public records act, one of these negotiations apparently saved $600,000 when the committee was able to trim an $8 million change order request down to $7.4 million.

The minutes also reflect that since its creation, the TBPOC has approved change orders totaling at least $509 million. Included in that total are millions for increased cost of materials—primarily steel and additional fabrication and contractor incentive payments related to superstructure problems. This additional money is covered by a $900 million contingency fund established by the Legislature in 2005.

Ultimately all change orders greater than $1 million always come to the TBPOC, which tells Caltrans whether to approve them or not. Because all TBPOC decisions are reflected in the monthly reports and the minutes are public records, details of committee activities are publicly available, albeit in an abridged, difficult-to-obtain way.

The ball is now in the lawmakers’ court. Heminger said the TBPOC produces and sends the reports to Sacramento, but they can’t make lawmakers read them.

Following the ebb and flow of the contingency fund in these monthly reports takes a bit of skill, as the numbers don’t necessarily reflect what’s been spent or what’s earmarked.

Despite continuing attempts to contain costs, spending oversight by state auditors and the Legislature had ended in 2005. Indeed, for the past five years the closed-door nature of decision-making has shrouded many major project developments from public view.

Mayhew said BATA conducts audits of Caltrans’ payment process every other year, and audits actual payments every other quarter. Normally, Mayhew said, BATA accountants would conduct a beginning, interim, and ending audit, but for this project it audits on a much more frequent basis.

In an unusual move, when they created the TBPOC, the Legislature exempted the committee from California’s open meetings laws, which require government business to be conducted in public.

The three TBPOC committee members meet out of the public eye in a variety of locales, even holding meetings in Shanghai when they travel to China to inspect the steel fabrication for the suspension span. The most recent trip was in August. Meetings are also held at the Port of Oakland, Caltrans headquarters in Sacramento, and the state Capitol, among other locations.

Why would directors charged with bringing a degree of transparency and sunshine to the project need to operate behind closed doors?

State Sen. Mark DeSaulnier, a Contra Costa County Democrat who served on the MTC during the tumultuous debates of 2005, said it was a mistake to make TBPOC meetings private.

“You have to consider where we were before we did this,” he said. “There was little oversight and there were delays and overruns. The problem with the design team is that it’s not transparent enough. There should have been more transparency, and we should have been more aggressive about the process.”

Rentschler, from the MTC, defended the closed meetings, saying they have helped keep costs under control.

“The TBPOC deals with contractor negotiations that are really high-dollar issues,” he said. “They have to be able to do this in a way where contractors cannot see the public’s hand. Otherwise everything is going to cost us twice as much.”

“Giving people prompt information about the decisions we’ve made is fulfilling our mandate to be transparent,” he added. “I don’t think it makes sense to extend that mandate into our negotiating discussions.”

Kempton, the former Caltrans director and a member of the TBPOC until last summer, said the TBPOC made sure that the Bay Bridge project wasn’t conducted according to Caltrans’ “business as usual” approach. With three bosses, he said, all of the information must be provided before decisions are made.

He endorsed the TBPOC’s accountability through regular reports. “It is what it is,” said Kempton, the former TBPOC chairman. The TBPOC was set up as a collaborative form for the major partners, he said. “It was certainly not the intent to be secretive.”

QUESTIONS OF QUALITY IN CHINA

When Caltrans awarded the final east span bid on April 18, 2006—100 years to the day after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake—the winner was a joint venture between two companies: American Bridge Company of Coraopolis, Penn. (a Pittsburgh suburb), the builder of the original Bay Bridge; and Fluor Enterprises Inc. of Dallas, Texas. The joint venture became known as ABF.

//In an unusual move, when they created the TBPOC, the Legislature exempted the committee from California’s open meetings laws, which require government business to be conducted in public. Why would directors charged with bringing a degree of transparency and sunshine to the project need to operate behind closed doors?//

A key element of ABF’s winning bid was its steel fabricator, the Shanghai Zhenhua Port Machinery Company (ZPMC), a subsidiary of China Communications Construction Company. ZPMC is the world’s largest manufacturer of the giant cranes used to load and unload ships at many of the world’s seaports, including the Port of Oakland. The use of Chinese steel and labor in fabricating the deck and signature tower of the self-anchored suspension span permitted ABF to reduce its bid by hundreds of millions of dollars.

While foreign fabrication may be less expensive, it creates problems of its own. For two years, Caltrans and ABF have been sending quality-control inspectors to ZPMC’s plant in Shanghai to oversee construction. A primary concern for the inspectors has been the level of training for the 2,000 Chinese workers on the project. These workers have been assigned to assemble the huge steel deck plates and tower sections that will form the suspension span. Problems with the integrity of these welds first began to surface in 2007 and surprised even members of the TBPOC. Orthotropic box girders, used to fashion the deck sections, are relatively common, albeit complex, in comparison with the tower itself, a structure engineers characterize as a “complete oddball.”

“We’ve had more trouble on the deck than the tower, and going into the project we thought it would be the other way around,” Heminger said.

That trouble may have been predicted as far back as 2005, long before the contract was even bid. A letter to Caltrans from Parsons Corporation, an engineering company, predicted difficulties with the box girder configuration.

“We have no doubt that quality can be achieved, but at what cost and impact to schedule remains uncertain,” the company wrote, adding that there were potential risks associated with the main cable design and fabrication.

Some of those grim forecasts have been realized, with more than a year of delays in shipping the box girders from Shanghai and requiring Caltrans to spend millions of dollars correcting the problem in an attempt to meet the 2013 target date for opening the new span.

It’s not that the steel is substandard, but it’s the miles worth of welds putting the steel pieces together that have exposed a weakness in the fabrication process.

During a February 2006 pre-bid audit, according to an internal Caltrans report obtained by a California Public Records Act request, the facility received a “contingent pass” because auditors anticipated construction of a new facility—devoted entirely to fabricating the tower—by the following spring and that ZPMC would purchase equipment necessary to comply with manufacturing requirements.

More than a year later, in a follow-up audit report from August 2007, Jim Merrill—then a senior engineer with Mactec, which assisted Caltrans with inspections until its contract expired last winter—wrote that Office of Structural Materials auditors expressed concern that “ZPMC does not have the required experience” or knowledge to fabricate this complicated type of bridge.

At the time, the fabricator was beginning work on its first orthotropic deck bridge—South Korea’s Incheon Bridge, a simpler cable-stayed bridge that was completed three months ago.

Tony Anziano, Caltrans’ engineer, described the difficult nature of the welding process: “It’s a controlled application of a bolt of lightning, if you will.”

Controlling that bolt of lightning, Anziano said, is a “delicate balancing act” of producing a weld that is deep enough to bond pieces of steel together without tearing through the deck plates. This same fragile fusion process delayed completion of the new Carquinez bridge for a year while the high-temperature arc-welding procedure used for fabricating that structure’s deck panels was being fine-tuned in Japan.

“In some cases, we’re a little more exacting than some pretty significant industries, even more so than the nuclear industry,” Anziano said. “It’s challenging. There’s always a learning curve and they [the Chinese] get better at it,” he added.

//“I’m a proud American, too,” one engineer said, but “the U.S. capacity to execute the fabrication of this structure is very much in doubt in my mind.”//

Heminger said that although the “learning process clearly has been slower than we would have liked,” the “learning is occurring,” because inspectors are not seeing earlier welding problems reappear.

John Fisher, a weld expert who has provided Caltrans with technical advice, said repairs are always part of the fabrication process.

“The fact that there are repairs is not a serious issue,” said Fisher, who has analyzed the Chinese welds. “The problem is that the fabricator is a little blasé about it,” relying on cheap labor to make repairs rather than preventing them, and that the amount of repairs has exceeded “what would probably be tolerated here in the U.S. and maybe even Europe.”

Because most of the fabrication work in China is performed manually, and due to cultural and language differences, there have been some problems with contract specifications.

Heminger said that any specification or standard requires some level of interpretation about how much is good enough and what constitutes compliance.

“We’ve all struggled with this question of interpreting the specs and the standards to make sure we all are in agreement,” he said. “No steel structure is free of imperfections, just as no concrete structure is free of imperfections. We need to avoid getting into a situation where we are searching for perfection because we’ll be over in China for 50 years doing that.”

Heminger said that an American firm would have faced similar problems.

“The simple fact is, despite the fact that we got a bid for domestic steel, I’m not sure that there is a domestic steel fabricator that could do what ZPMC is doing” in terms of scale and their capability for the “massivity of this project.”

“This is probably one of the most complex steel bridges that we’ve ever built,” with respect to the complications and the complexity of the fabrication, said Mike Flowers, a project manager for American Bridge. “I don’t think that anyone should assume that ZPMC, because they’re in China, is some third-world fabricator that’s not capable of executing complex work.”

He pointed out that few fabricators worldwide have the requisite experience building this type of deck, known as an orthotropic box girder.

“I’m a proud American, too,” Flowers said, but “the U.S. capacity to execute the fabrication of this structure is very much in doubt in my mind.”

While no stranger to large steel structures, ZPMC is relatively new to building bridges. They have been involved in two bridge-building projects previously. The company has fabricated steel for the Golden Ears Bridge in Vancouver, British Columbia, and Incheon Bridge in South Korea. But the Bay Bridge is the first ZPMC fabrication job with extraordinary requirements.

Although the new Bay Bridge span is being built to last well into the 22nd century, so long as a defect does not propagate or undermine structural integrity, which could lead to long-term maintenance problems, Heminger said there are some imperfections acceptable within the criteria.

“We did have some difficulty at the outset trying to agree on what was good enough,” Heminger said.

Both Caltrans and the contractor have attempted to formalize that process by introducing a “green tagging” process, whereby inspectors physically put a green tag on the steel, indicating it meets quality requirements.

Caltrans anticipated some of these challenges, requiring ZPMC to go through an exercise of constructing a prototype before work even began on the actual bridge sections.

Weld expert Fisher, a professor emeritus at Lehigh University’s civil engineering department, said that by building full-scale prototypes of difficult-to-access sections—like most of the tower components—Caltrans and the fabricator could “shake out and deal with some of the potential problems that would be encountered” later on.

To insure that fabrication meets standards, Caltrans and ABF collectively have 250 inspectors at ZPMC’s facility in Shanghai. Much of the cost for these additional personnel is being shouldered by ABF.

“They need to put the number of inspectors over there that they need to do the job, as do we,” Heminger said. “We’re paying for ours and they’re paying for theirs.”

When the TBPOC visited China in August 2009, Heminger said its presence was meant to reinforce the ultimate message that “although they hear constantly from us about the schedule, they should not mistake that for a willingness to sacrifice quality.”

“We’re not running a science project here,” he said. “We’re trying to build a bridge. The tolerances for fabricating the welds, the seismic performance and the sheer size of the project have called upon them to learn a lot of new techniques.”

Fourteen sections comprise the road deck in each direction, for a total of 28 box girders, and although the span’s tower visually gives the impression of a single support, it actually has four separate legs, each composed of five different pieces tied together to provide structural redundancy in the design. Thus any delay in delivery of the steel deck sections affects the erection of the entire suspension span—something that adds millions of dollars to the cost each month.

Despite the grinding pace of work at the ZPMC facility in Shanghai—a 24-hour-a-day, seven-day-a-week operation—the first steel shipment is expected to depart China this month. That’s 15 months behind the original target date of October 2008. It takes about a month for the barge to float its way across the Pacific, but longer in winter.

While weld inspections and crack repairs are stalling the process, that isn’t the only problem being encountered. Another complication is the debates among the bridge designer T.Y. Lin/Moffat Nichol, ABF, and Caltrans over how to translate the most complicated sections of the bridge deck from design drawings to an actual steel structure.

Due to the specialized nature of designing welded connections, only a small number of firms have the expertise to take structural design drawings and convert them into production blueprints used by fabricators—“shop drawings,” as they are known. For the Bay Bridge suspension span, this translation is being done by the joint venture of Vancouver’s Candraft Detailing Inc. and Tensor Engineering of Indian Harbor Beach, Fla.—making it difficult to get the structural designers in America and Canada together in the same room.

In part because of the geographical separation, and in part because of the engineering challenges posed by connections where the suspension span meets the concrete skyway, finger-pointing among the parties adds its own costs to the project.

Just how much cost this arguing will add remains to be calculated. However, members of the TBPOC discussed the problem at a meeting last June, where they concluded that despite “dramatic improvements” during the first six months of 2009, the shop drawing approval process continues to impede progress. The committee approved $3 million in partial payment for design changes to shop drawings.

At an August meeting, as committee members were planning trips to Canada and China in an effort to resolve the continuing problems, the TBPOC was told finger-pointing persisted and it was now “imperative” that all parties be put together in the same room.

Last month Heminger said he believed the committee had “broken the back of the problem,” but there was still a considerable amount of work to be accomplished in completing drawings that are crucial to the project. He said there would be a delay in the planned phased opening of traffic in at least one direction.

“It’s unlikely that we will be able to make 2012 for westbound,” Heminger said, “but we’re still hopeful that we can make 2013 for both west and east.”

THE ROAD FROM HERE

When the first gigantic pieces of steel decking for what will become the Bay Area’s newest icon finally plow their way across the Pacific Ocean from China early next year, Caltrans’ ship will have finally come in. The arrival will mark not only a coveted milestone in what has become the state’s most expensive single public works construction project, but lend credence to Shakespeare’s mostly forgotten metaphor “what’s past is prologue.”

There may not be flotillas of fireboats and sailboats greeting the steel as it drifts under the Golden Gate, the Bay Area’s most famous landmark, but it’s almost certain scores of engineers and public officials will be reveling in some measure of satisfaction that the final pieces of a project more than two decades in the making are finally starting to come together.

//Despite California’s sometimes-dysfunctional government and the state’s increasing inability to live within its financial means, if you can squeeze enough money from motorists who are dependent on bridges for their own livelihood, even the most sophisticated bureaucratic squabbling, infighting, and outright bumbling will ultimately give way to progress.//

The arrival will also signal something else: that despite California’s sometimes-dysfunctional government and the state’s increasing inability to live within its financial means, if you can squeeze enough money from motorists who are dependent on bridges for their own livelihood, even the most sophisticated bureaucratic squabbling, infighting, and outright bumbling will ultimately give way to progress.

While few will argue that the Bay Bridge’s new east span is not an engineering marvel, there are many who will complain about the $6.3 billion construction price tag that will almost certainly be marked-up this week. Certainly the Bay Bridge east span replacement isn’t costing anywhere near the estimated $22 billion Massachusetts residents will be expected to ultimately pay for Boston’s “Big Dig.” But for a state in the throes of increasingly severe budget problems, high unemployment and very little light at the end of the fiscal tunnel, the mere fact the new span might just open in 2013 could be solace enough for commuters who will be paying at least $5 for the privilege of driving across its sweeping expanse without having to worry about being crushed by falling metal, or being hurled into the bay when the next earthquake strikes.

Virtually no bridge-building project is without its share of indecision or politics. Even during construction of the original Bay Bridge, engineers and architects argued over what color to paint the structure—a dispute that was somewhat innocuous in terms of structural stability and safety, but something of a harbinger of things to come more than a half-century later, when it was decided to replace the eastern portion of the bridge altogether.

The question then was simply, would the new bridge be black or gray? C.H. Purcell, the structure’s chief engineer, believed dressing the bridge in the wrong color would scar the prized vistas for decades to come. In a Los Angeles Times article published 21 months before the November 1936 ribbon cutting, Purcell argued the bridge should be painted black so it could be seen. “Don’t they paint battleships gray so that you can’t see them so well?” he asked. Purcell lost that battle—the west span is gray, just like other bridges named for dead people, such as New York City’s George Washington Bridge and Philadelphia’s Benjamin Franklin Bridge.

The new east span will be much more beautiful than its drab predecessor—and, according to engineers, much safer, having the ability to withstand a major earthquake to come. If the east span design is a visible architectural masterpiece justifying the political meddling that stalled its construction for years and increased its price by billions of dollars, its structural integrity is an invisible engineering marvel tailored to mitigate the seismic risk of the bay’s treacherous soil conditions that will be particularly susceptible to the strong shaking of a major temblor on the San Andreas or Hayward faults—something that is predicted to occur during the bridge’s estimated 150-year lifetime.

Just like the existing span, the new replacement is not anchored on bedrock that lies thousands of feet below murky bay waters. For this reason, Caltrans produced a more complete picture of what lurks below the surface, supplementing the outdated existing body of knowledge by conducting a whole new series of soil tests near each and every foundation, studies that required boring down into the soil over 350 feet in some cases. These tests played a big part in the ultimate decision on the type of new bridge that would be constructed.

In the early stages of planning, recalled the MTC’s Rentschler, the process was that of many “civic champions essentially being in the way, being obstructionists, using the Bay Bridge for other ends.” Politicians and transportation planners didn’t want to accept that the Bay Bridge replacement was really about a seismic safety job and not about reintroducing rail service to the East Bay, something that existed in the form of BART’s transbay tube long before a new east span was even contemplated. Another rail project, the proposed high speed rail network, with a link between San Francisco and Los Angeles, is in the planning stages and will be another megaproject expected to be completed by 2030—with initial funding through a $10 billion bond issue approved by voters in 2008.

What the ultimate cost of a fast train ride between Northern and Southern California will be is anybody’s guess. Although estimated to run nearly $20 billion with interest, it’s almost certain to go over budget like most other major transportation construction projects—including the Bay Bridge.

Politics and steel don’t always mix in cost-effective ways. One plays to the public perception, the other to the public safety.

The bottom line, says former state Secretary of Business, Transportation, and Housing Sunne McPeak: “Never let politicians design a bridge.”

This story is part of a special reporting project that first appeared Dec. 8, 2009, in the San Francisco Panorama, a single-edition broadsheet newspaper published by McSweeney's. The project, conducted by SF Public Press, was researched and written by Patricia Decker and Robert Porterfield with the assistance of Mike Adamick, Andrew Bertolina, Richard Pestorich and Michael Winter. The project was supervised by Public Press director Michael Stoll. More than 140 people helped to fund this reporting project by donating through Spot.Us.